What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

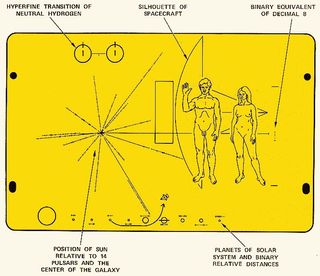

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

- Become A Member

- Gift Membership

- Kids Membership

- Other Ways to Give

- Explore Worlds

- Defend Earth

How We Work

- Education & Public Outreach

- Space Policy & Advocacy

- Science & Technology

- Global Collaboration

Our Results

Learn how our members and community are changing the worlds.

Our citizen-funded spacecraft successfully demonstrated solar sailing for CubeSats.

Space Topics

- Planets & Other Worlds

- Space Missions

- Space Policy

- Planetary Radio

- Space Images

The Planetary Report

The search for life.

How life on Earth shapes the hunt for life out there.

Get Involved

Membership programs for explorers of all ages.

Get updates and weekly tools to learn, share, and advocate for space exploration.

Volunteer as a space advocate.

Support Our Mission

- Renew Membership

- Society Projects

The Planetary Fund

Accelerate progress in our three core enterprises — Explore Worlds, Find Life, and Defend Earth. You can support the entire fund, or designate a core enterprise of your choice.

- Strategic Framework

- News & Press

The Planetary Society

Know the cosmos and our place within it.

Our Mission

Empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration.

- Explore Space

- Take Action

- Member Community

- Account Center

- “Exploration is in our nature.” - Carl Sagan

Jake Rosenthal • Jan 20, 2016

The Pioneer Plaque: Science as a Universal Language

In 1972, an attempt to contact extraterrestrial life was cast into space with the launch of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft. This space vehicle was designed to explore the environment of Jupiter, along with asteroids, solar winds, and cosmic rays. Among a succession of firsts achieved by the spacecraft, Pioneer 10 would attain enough velocity to escape the solar system. This tacked on yet another first: the possibility of the interception of a human machine by an extraterrestrial civilization, providing us the opportunity to make contact with life from another world.

The suggestion of a message on Pioneer 10 was brought to Dr. Carl Sagan mere months before launch—a staggeringly brief period in the timescale of the design and test of spacecraft. Sagan passed along the idea to NASA, and to his surprise, the suggestion was embraced and approved by every level of the hierarchy. At that, Sagan joined Professor Frank Drake of Cornell University and, Sagan’s then-wife, artist Linda Salzman Sagan, to craft this extraterrestrial message. How would this great undertaking be fulfilled? What would we say? What in our roughly five-thousand-year recorded history needs to be said to tell the universe who we are? And how would we say it?

Humans speak nearly seven thousand languages, some with multiple dialects. The countless other species on Earth communicate with innumerably more, nearly all of which we have, thus far, failed to understand. By extrapolation, it is presumable that an alien language is different than any language we have developed. Human languages are products of human minds, and thereby, can be understood by human minds, by means of human senses—sight, sound, touch. How could we begin to imagine an extraterrestrial language if we cannot imagine with what senses the beings communicate? They may not have vocal chords with which they produce sounds or ears with which they capture them. So we must rely on universally-understood concepts, and devise a communication method neither specific to location nor species nor world. Perhaps, the only similarity between our species is the universe in which we both live. Thus, the language we are most likely to share is the study of the universe itself: science. The result of this conclusion was the Pioneer Plaque.

The Pioneer Plaque is a physical, symbolic message affixed to the exterior of the Pioneer 10 spacecraft. At the core of this message is a fundamental concept that establishes a standard of distance and time, which, thereafter, is employed by the other components of the plaque. The design team postulated that hydrogen, being the most abundant element in the cosmos, would be one of the first elements to be studied by a civilization. With this in mind, they inscribed two hydrogen atoms at the top left of the plaque, each in a different energy state. When atoms of hydrogen change from one energy state to another—a process called the hyperfine transition—electromagnetic radiation is released. It is this wave that harbors the standard of measure used throughout the illustrations on the plaque. The wavelength (approximately 21 centimeters) serves as a spatial measurement, and the period (approximately .7 nanoseconds) serves as a measurement of time. The final detail of this schematic is a small tick between the atoms of hydrogen, assigning these values of distance and time to the binary number 1.

The most prominent figures on the plaque are those of two adult humans: a man and woman. The man bends his arm and displays an open palm—an international greeting, but one that, admittedly, may be meaningless to an extraterrestrial civilization. The woman hangs her arms by her sides and stands with her weight shifted rearward as to dispel any misunderstandings regarding a fixed body and limb position; we are mobile and flexible. Beside the illustrations of the humans is the binary number 8, inscribed between two ticks, indicating the height the woman. The civilization could then conclude that the woman is 8 units tall, the unit being the wavelength (21 centimeters) described by the hyperfine transition key; thus, the woman is 8 times 21 centimeters, or about 5.5 feet tall.

At the heart of the plaque is an array of lines and dashes—a cosmic address on the interstellar letter. In the center is our home star; the radial spokes signify the relative distances and directions to pulsars—rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit electromagnetic radiation at regular intervals. Accompanying each line is the period of the respective pulsar—once again, in binary. Not only does this map communicate position, but time as well—an epoch in the lifetime of the universe during which the message was sent. The rate of electromagnetic bursts from pulsars changes over time; thus, the period of the pulsars denoted on the plaque serves as a timestamp. It is presumed that a civilization that has developed radio astronomy will have the capability to comprehend the nature of pulsars. Given the information presented in the pulsar map, it is feasible that such a civilization could date back the message and triangulate our position. As further confirmation of our locale, our solar system’s planets (nine at the time) are depicted in the bottom margin of the plaque with their respective distances to the sun in binary. Supposedly, in the history of the Milky Way, only one star has ever fit the characteristics displayed on the plaque.

The last signal from the Pioneer 10 spacecraft was received on January 22, 2003; NASA reported that the power source had depleted. Although the spacecraft can no longer speak to us, it presses onward—it now speaks for us. As interstellar courier, it bears the accumulated voice of every human, transcribed in, perhaps, the only common language in all the cosmos. We are but cosmic toddlers just learning how to take our first steps into space, and just learning how to speak to the universe.

Since Pioneer 10 was directed neither to an exoplanet nor a star, contact is extremely unlikely. But if, by the merest happenstance, the spacecraft is intercepted by an alien species, there is at least a chance that the species can interpret our message. In all likelihood however, Pioneer 10 and its plaque will be lost in the immense tranquility of empty space. But in no case was our attempt for naught. Pioneer 10 remains more than just a ghost of a ship, and the plaque is more than a shout into the void. The message we sent to the universe still echoes in our ears. Born from such a mission—one that spans space, time, and perhaps, civilizations—is a new mindset, an otherworldly perspective.

From the vantage of a distant world, our sun will be just another star, and our planet hidden in the radiance of the stellar glow. On such a world—one so distant and different from our own—we have not the slightest indication of what life will be like, how it began, how it evolved. If beings were to emerge, we know not their anatomy nor biology nor psychology, their physical traits, their sensory capabilities, their intellectual sophistication, their disposition; more or less, we are blind to every aspect of their species. They could be different in every way—in ways we have yet to understand or could even imagine. We make numerous assumptions about what life is and what life is not—educated guesses based off a sample size of one. But if, in some form or another, advanced consciousness arises elsewhere in the cosmos, it is possible that those beings will wonder, as we did: What are the lights in the sky? Where did the planets come from? What else is out there? Who else is out there? They may compile a system of knowledge of the cosmos and the laws that govern it; we call this “science.” About this hypothetical species, we know but one thing: the science they develop—the natural laws they discover—if they were to do so, would be exactly the same as our own.

Although not every human conducts science, it is conducted for every human. Science speaks to all of us in a way nothing ever has. It sparks new ideas and alternate perspectives. It brings each of us together and all of us forward. It is, at the very least, an international language, because there is an implied assertion with every question: there is something we do not know; and with our missions, we learn together. We probe the unknown looking for answers, venturing to understand the universe as it is—not the way we want it or believe it to be. Every step of the way, we strive not to fit the universe to the limits of our minds, but stretch our minds to the limitlessness of the universe.

For every great scientific discovery and technological advancement, there was a time before, when the universe was a little less known. The significance and brilliance of our technologies and the science that drives them is too often overlooked. We forget the time before—a time without cell phones and personal computers, automobiles and airplanes—during which we wondered what it would be like to communicate at the speed of light and fly around to the other side of the planet in a matter of hours. Right now, at this time, we wonder what it would be like to find life elsewhere in the cosmos and to make first contact. This is the time before that great discovery, and there will be a time after. Maybe in the near future, or maybe a more distant one, it will be commonplace to carry on conversations with extraterrestrials; and again, we will forget how, right now, we are ceaselessly wondering, in endless search for an answer.

A Message from Earth , by Carl Sagan, Linda Salzman Sagan, and Frank Drake

The Cosmic Connection , by Carl Sagan

PIONEER 10 SPACECRAFT SENDS LAST SIGNAL , by Michael Mewhinney

Take action for space exploration!

Give today to have your gift matched up to $75,000.

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Here are instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser .

Pioneer 10: Greetings from Earth

Pioneer 10 was a breakthrough mission, accomplishing several firsts among spacecraft. It was the first to fly beyond Mars, the first to fly through the asteroid belt, first to swing by the planet Jupiter, and first to leave the solar system. Along the way, the spacecraft even generated a mystery of its own – the Pioneer Anomaly – that took decades for scientists to solve.

Thanks to Pioneer 10's pictures, the planet Jupiter and its moons , which were formerly only small circles in a telescope, became large, vibrant worlds in the eyes of scientists. For decades after those images beamed back to Earth, Pioneer 10 kept going. It sent valuable scientific data about the sun and cosmic rays before its signal became too faint for Earthlings to hear.

Pioneer 10 also carries a plaque with a message to any intelligent life it might encounter on its journey. The Pioneer plaque includes diagrams of Earth's location and drawings of a man and a woman.

Instruments and art

- Pioneer 11: Up Close with Jupiter & Saturn

- Voyager Spacecraft: Beyond the Solar System

Launched on March 2, 1972, Pioneer 10 was the latest in a series of missions to explore space, which was still a very new frontier at the time. The earliest Pioneers aimed for the moon, while later generations forged farther and farther into space.

This spacecraft, powered by four radioisotope thermoelectric generators, measured 9.5 feet (2.9 meters) long and weighed 570 pounds (258 kilograms). Among the instruments and camera equipment on board, Pioneer also carried something special: a six- by nine-inch (15.2 by 22.8 centimeters) gold plaque.

The plaque depicts two nude figures – a man and a woman – along with diagrams of the solar system and the sun's position in space. It was intended to serve as a map to Earth for any extraterrestrials who might be curious about who made the spacecraft.

Two people designed the plaque: famed television host and astronomer Carl Sagan , and Frank Drake , founder of SETI and author of an equation that measures the likelihood of communicating with intelligent life.

Imaging Jupiter

Pioneer 10's primary target was the planet Jupiter . It launched from Earth on an Atlas-Centaur three-stage launcher, intended to boost the spacecraft to 32,400 mph (52,142 kph). Sailing away from Earth faster than any spacecraft before it, Pioneer soared by the moon just 11 hours later and made it past Mars in only three months.

Perhaps Pioneer's most dangerous phase was the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, which it reached on July 15. Pioneer faced the risk of colliding with bits of asteroids, anywhere from the size of a small particle to rocks as big as the state of Alaska, according to NASA. But it made it safely to the other side and reached Jupiter on Dec. 3, 1973.

Pioneer 10 was just intended to be a scout for future missions, so its stay at Jupiter was brief. It came within 81,000 miles (130,000 kilometers) of the surface as it sailed past. Pictures beamed back to Earth revealed Jupiter as a liquid giant, while other instruments recorded information on Jupiter's radiation belts and magnetic fields.

The spacecraft also sent back snapshots of some of Jupiter's moons. Although the shots were taken from a distance, scientists could pick out shadows and featureson Europa , Ganymede , Io and Callisto . It was incredible resolution compared to the almost 400 years of observations previously done through telescopes.

On through the outer solar system

Pioneer's story does not end there. For about a quarter-century, the little spacecraft flew farther and farther away from Earth and continued producing science. It measured particles streaming from the sun, and cosmic rays incoming from outside the solar system.

Along with sister ship Pioneer 11, the spacecraft also embroiled scientists in an intergalactic mystery. For decades, NASA was puzzled as to why the two probes travelled 3,000 miles (4,828 km) less than projected, every single year.

Dubbed the "Pioneer Anomaly," it was only in 2012 that NASA found out what happened : heat flowing through the spacecrafts' power systems and instruments was pushing back on the Pioneers as they moved out of the solar system.

NASA concluded Pioneer's science mission on March 31, 1997, but kept track of the spacecraft through the Deep Space Network . Obtaining its signal was used as training for flight controllers looking to get data from the Lunar Prospector mission, which flew for 19 months before being deliberately crashed into the moon's surface in 1999 .

Pioneer 10 last sent data back to Earth on April 27, 2002. Its decaying signals were just too faint for NASA's antennas to pick up anymore.

As far as we know, the spacecraft sails on. NASA warmly refers to Pioneer 10 as a " ghost ship " of the outer solar system as the spacecraft coasts in the general direction of Aldebaran – the eye of the bull in the constellation Taurus.

Residents of that region of space will need to be patient if they want to see Pioneer 10. NASA expects it will take the spacecraft 2 million years to traverse the 68 light-years of space to Aldebaran.

— Elizabeth Howell, SPACE.com Contributor

- Jupiter, Largest Planet of the Solar System

- Carl Sagan: Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot & Famous Quotes

- NASA's 10 Greatest Science Missions

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, " Why Am I Taller ?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin endorses Trump for president

SpaceX launches 23 Starlink satellites from Florida (video, photos)

Comets, supermoon, northern lights, oh my! Amazing photos of the celestial Halloween treats of October 2024

Most Popular

- 2 Will China return Mars samples to Earth before the US does?

- 3 Can 'failed stars' have planets? James Webb Space Telescopes offers clues

- 4 NASA astronaut snaps spooky photo of SpaceX Dragon capsule from ISS

- 5 Apollo 11 moonwalker Buzz Aldrin endorses Trump for president

IMAGES

VIDEO