It seems JavaScript is either disabled or not supported by your browser. To view this site, enable JavaScript by changing your browser options and try again.

Jump to main content

- Please note: The Academy will close at 3 p.m. on Sat., Oct. 26, for SuperNatural . 1

Science News

Secrets of great white shark migration.

For Shark Week, we’re rediscovering some of our favorite shark articles from the past. This post was originally published in 2013.

Studies of bears and sea lions have enabled us to understand how these mammals reserve energy in the form of fat and blubber, sustaining them through winter or allowing them to travel great distances. And they aren’t alone in facing such physical challenges. Great white sharks also need a way to store energy during their long migrations, but until recently, this specific mechanism was unknown. (Maybe no one wanted to get too close to them…)

Great white sharks migrate between foraging and reproductive areas, traveling over 2,500 miles annually. While they are not known to be picky eaters, there is little food available far out in the Pacific Ocean.

Researchers at Stanford University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium studied how great whites could accomplish such a journey while fasting. But again, because great whites are, shall we say, just a wee bit dangerous, scientists needed to find ways to study the sharks’ lives without risking their own.

“The most difficult thing about this research was finding a way to bring all of the different sources of data together into a coherent and robust story,” says Gen Del Raye, a Stanford undergraduate who initiated the project. He knew that if they succeeded, they might shed light on storage strategies for other ocean animals.

First the team studied a (well-fed) great white shark living at the Monterey Bay Aquarium . Over time the shark gained mass (but still maintained its flattering, streamline figure) and simultaneously increased in buoyancy.

Next the researchers pulled data from shark archival tags . Shark location information is time-stamped, enabling researchers to focus on one specific behavior, “drift-diving.” Huge marine animals sometimes act like hang gliders—they relax their fins while currents and momentum carry them forward. Drift-diving data provided the final clue to the research team: they established that migrating sharks lost buoyancy over time.

By measuring the rate at which sharks sink during drift dives, the researchers were able to estimate the amount of oil in the animals’ livers, which accounts for up to a quarter of their body weight. Sharks store oil before migration (making them float) then gradually use that energy throughout their journey (making them sink).

“Sharks face an interesting dilemma,” says Sal Jorgensen, a research scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. “They carry a huge store of energy in the form of oil in their massive livers, but they also depend on that volume of oil for buoyancy. So, if they draw on those reserves, they become heavier and heavier.”

The research paper might not only be used to help solve mysteries about other marine animals, but can also be used to assist conservation efforts around coastal feeding grounds.

“We have a glimpse now of how white sharks come in from nutrient-poor areas offshore, feed where elephant seal populations are expanding—much like going to an Outback Steakhouse—and store the energy in their livers so they can move offshore again,” says researcher Barbara Block , a professor of marine sciences and a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. “It helps us understand how important their near-shore habitats are as fueling stations for their entire life history.”

Image: Pterantula /Wikipedia (Terry Goss)

Related science news

Seven questions with Dr. John McCosker, Senior Scientist and Chair of the Department of Aquatic Biology.

Emeritus Chair of Aquatic Biology, McCosker studies white sharks and the marine life of the Galápagos Islands.

Get an extra month of incredible science—free!

With 60,000 animals, 365 days of free admission, and dozens of member programs and perks, we think that free 13th month might come in handy.

Discovering All Marine Species

Great White Shark Migrations: The Latest Research

Great White Shark Migrations: Discover the fascinating world of Great White Sharks and their incredible migratory patterns. In this article, we delve into the latest research that sheds light on their long-distance journeys and the factors influencing their movements. Join us as we unravel the mysteries surrounding these apex predators and uncover new insights into their behavior. Stay tuned for an unforgettable journey into the realm of the majestic Great White Sharks.

Table Of Content

- 1 Insights into Great White Shark Migrations: Unveiling the Latest Research Findings

- 2 The Causes of Great White Shark Migrations

- 3 Tracking Great White Shark Movements

- 4 Patterns of Long-Distance Migrations

- 5 The Role of Breeding Grounds in Migrations

- 6 Implications for Conservation

- 7.1 How far do great white sharks migrate and what factors influence their migratory patterns?

- 7.2 What is the purpose of great white shark migrations and how do they benefit the species?

- 7.3 Are there specific regions or hotspots where great white sharks are known to gather during their migrations, and if so, what makes these areas attractive to them?

Insights into Great White Shark Migrations: Unveiling the Latest Research Findings

Insights into Great White Shark Migrations : Unveiling the Latest Research Findings

Understanding the migration patterns of Great White Sharks is crucial for marine scientists and conservationists. Recent research has provided valuable insights into their movements and behavior, shedding light on their incredible journeys.

One key finding is that Great White Sharks undertake long-distance migrations, spanning thousands of miles. They have been observed traveling across entire ocean basins, from feeding grounds to breeding areas and back.

Satellite tagging has played a vital role in tracking these migrations. By attaching tags to individual sharks, researchers can monitor their movements in real-time. This technology has revealed some astonishing facts about the behavior of Great Whites.

For instance, studies have shown that male and female sharks exhibit different migration patterns. Females often migrate for reproductive purposes, journeying to specific regions known as nurseries where they give birth to their young. On the other hand, males tend to move around more extensively, traversing large distances in search of prey and potential mates.

Another interesting discovery is the existence of «hotspots» along migration routes. These are areas where Great Whites congregate in high numbers, indicating the importance of these locations in their annual journeys. Identifying and protecting these hotspots is crucial for ensuring the conservation of this iconic species.

Additionally, research has revealed that Great White Sharks display remarkable navigational abilities. Despite covering vast distances, they are able to return to the same feeding or breeding grounds year after year. It is believed that they rely on a combination of environmental cues, such as magnetic fields and ocean currents, to navigate accurately.

Understanding these migration patterns is essential for effective management and conservation efforts. By safeguarding crucial habitats, reducing human impacts, and promoting sustainable fishing practices, we can help protect Great White Sharks and ensure their survival for future generations.

In conclusion, ongoing research continues to unveil fascinating insights into the migrations of Great White Sharks. By harnessing technology, scientists are gaining a deeper understanding of their behavior, habitat preferences, and navigational abilities. This knowledge is essential for implementing conservation strategies that will safeguard these magnificent creatures and the delicate marine ecosystems they inhabit.

The Causes of Great White Shark Migrations

The migrations of Great White Sharks are driven by a variety of factors, including seasonal changes in water temperature and prey availability . These factors influence the distribution of their preferred food sources and trigger the sharks to move to different areas.

Tracking Great White Shark Movements

Scientists have been using satellite tagging and acoustic telemetry to track the movements of Great White Sharks. This technology allows researchers to monitor the sharks’ activity patterns, migration routes, and preferred habitats.

Patterns of Long-Distance Migrations

Research has shown that some Great White Sharks undertake impressive long-distance migrations , traveling thousands of miles across oceans. These migrations often occur during specific times of the year and appear to be related to breeding, feeding, or seasonal changes in habitat.

The Role of Breeding Grounds in Migrations

Great White Sharks are known to migrate to specific breeding grounds , where they engage in courtship behavior and mate. These breeding grounds, such as the waters off the coast of South Africa and California, serve as crucial stopovers in their migratory routes.

Implications for Conservation

Understanding the migratory patterns of Great White Sharks is essential for their conservation. By identifying their critical habitats and migration routes, scientists can advocate for the establishment of marine protected areas and implement measures to reduce human impacts on these vulnerable species.

How far do great white sharks migrate and what factors influence their migratory patterns?

Great white sharks are known to undertake impressive long-distance migrations. They can travel thousands of miles across oceans, but the specific distance and patterns vary among individuals. These migrations are influenced by several factors, including the availability of prey, water temperature, breeding behavior, and seasonal changes. Prey availability plays a significant role in great white shark migrations. They tend to follow their main prey, such as seals and sea lions, as they move along the coastline or migrate to different feeding grounds. Water temperature is another influential factor. Great white sharks prefer cooler waters, so they often migrate to areas where the temperature suits their needs. For example, during the summer months, they may follow colder currents towards higher latitudes, while moving towards warmer waters during winter. Breeding behavior also affects their migratory patterns. Female great whites, for instance, may migrate to specific mating grounds, where they can find suitable partners and reproduce. Lastly, seasonal changes can influence their movements. Some populations of great white sharks travel closer to shore during certain times of the year, while others venture further offshore. Overall, the migratory patterns of great white sharks are complex and vary depending on multiple factors.

What is the purpose of great white shark migrations and how do they benefit the species?

The purpose of great white shark migrations is still not fully understood, but researchers believe there are several reasons behind their seasonal movements. It is important to note that these migrations greatly benefit the species and play a crucial role in their survival.

Feeding: One major reason for great white shark migrations is to follow their prey. These sharks primarily feed on seals and sea lions, which are abundant in certain areas during particular times of the year. By migrating to these areas, the sharks can take advantage of the high concentration of prey, ensuring they have enough food resources.

Breeding: Another significant reason for migrations is reproduction. Female great white sharks tend to migrate to specific areas known as mating grounds, where males congregate, to find suitable mates. These areas may offer better opportunities for successful reproduction.

Temperature and Seasonal Changes: Great white sharks are ectothermic, meaning their body temperature is regulated by the environment. They tend to prefer cooler water temperatures. During colder months, they migrate to warmer waters, such as those found off the coasts of Mexico and Hawaii. When the water becomes warmer, they move towards cooler regions, such as coastal areas with upwelling currents. This migration helps them maintain their preferred body temperature range and optimize their metabolic efficiency.

Genetic Diversity: Migrations also play a role in maintaining genetic diversity within the great white shark population. By moving between different regions, individuals from various genetic backgrounds have the opportunity to mix and reproduce, preventing inbreeding and ensuring the overall health and adaptability of the species.

In summary, great white shark migrations serve multiple purposes, including following abundant prey, finding suitable mates, regulating body temperature, and maintaining genetic diversity. These movements are essential for the survival and well-being of the species.

Are there specific regions or hotspots where great white sharks are known to gather during their migrations, and if so, what makes these areas attractive to them?

Great white sharks are known to gather in certain regions or hotspots during their migrations. These areas are attractive to them for a few reasons.

One of the main attractions for great white sharks is the abundance of prey. They are known to commonly gather near coastal areas that are rich in marine life, such as seal colonies or areas with high concentrations of fish. These prey sources provide a reliable food source for the sharks.

Another factor that makes certain areas attractive to great whites is the water temperature and conditions. They prefer cooler waters, typically ranging from 12-24 degrees Celsius (54-75 degrees Fahrenheit). Some of the well-known hotspots for great white sharks include the coastlines of California, South Africa, Australia, and Guadalupe Island in Mexico.

These areas also offer favorable environmental conditions for the sharks, such as adequate salinity levels, suitable currents, and appropriate depth for hunting. Great whites are known to be highly adaptable and are often found in coastal, shelf, and deep oceanic waters.

Furthermore, some studies suggest that these gathering spots might also serve as mating and breeding grounds for great white sharks.

Overall, the specific regions or hotspots where great white sharks gather during their migrations are typically characterized by abundant prey, suitable water temperatures, and favorable environmental conditions.

In conclusion, the latest research on Great White Shark migrations emphasizes the remarkable and complex journeys undertaken by these apex predators. The findings shed light on their extensive movements across vast distances and highlight their crucial role in maintaining the health of marine ecosystems. The data gathered through advanced tagging technologies provide valuable insights into their behavior, feeding patterns, and habitat preferences. Understanding the migratory patterns of Great White Sharks is essential for implementing effective conservation measures and ensuring the long-term survival of these magnificent creatures . It is our responsibility to protect their habitats and promote sustainable fishing practices to preserve the delicate balance of our oceans . Let’s continue supporting further research efforts to uncover more about these incredible creatures and create a future where humans and sharks can coexist harmoniously.

Deja un comentario Cancelar la respuesta

The Great Migration: How Do Great White Sharks Migrate?

Each year, great white sharks embark on incredible journeys that take them across thousands of miles of open ocean. From the shores of South Africa to the beaches of California, these apex predators navigate a world without borders, driven by a range of factors that scientists are only just beginning to understand.

In this blog post, we’ll take a closer look at the world of great white shark migration, exploring the routes they take, the factors that drive their movements, and the incredible adaptations that allow them to travel such vast distances. Whether you’re a seasoned marine life enthusiast or simply curious about the wonders of the underwater world, this post will provide a fascinating glimpse into one of nature’s most awe-inspiring phenomena. So come with us on a journey to discover the incredible world of great white shark migration!

Great white sharks are known for their impressive long-distance migrations, with some individuals traveling thousands of miles each year. Scientists are still studying the exact mechanisms behind great white shark migration, but they believe that the sharks use a combination of environmental cues, such as changes in water temperature and magnetic fields, to navigate their way across vast distances. Great white sharks are also known to follow specific migratory patterns that coincide with the movement of their prey, such as seals and other marine mammals.

Table of Contents

Why Do Great White Sharks Migrate?

Great white sharks are among the most prolific migrators in the animal kingdom, traveling vast distances across the ocean each year. But what drives these movements, and why do great white sharks migrate?

Factors That Drive Great White Shark Migration

The migration patterns of great white sharks are influenced by a range of factors, including food availability, water temperature, and breeding cycles. In general, great white sharks tend to follow the movements of their prey, which include a variety of marine animals such as seals, sea lions, and other fish.

Water temperature also plays a key role in great white shark migration. These predators prefer cooler waters and are known to follow temperature gradients in search of optimal conditions. For example, in South Africa, great white sharks tend to move northwards during the summer months as the water temperatures become too warm for their liking.

The Importance Of Mating And Reproduction In Migration Patterns

Another key factor driving great white shark migration is mating and reproduction. Female great white sharks are known to migrate to specific regions to give birth to their young, while males follow these movements in search of potential mates.

Interestingly, different populations of great white sharks exhibit different mating and breeding behaviors. For example, in South Africa, great white sharks tend to mate during the winter months, while in California, mating tends to occur during the summer.

Examples Of How Great White Shark Migration Differs Between Populations

It’s worth noting that not all great white shark populations exhibit the same migration patterns. For example, while great white sharks in South Africa tend to migrate northwards during the summer months, those in California tend to move southwards during the same season.

Similarly, great white sharks in Australia have been observed to undertake long-distance migrations of up to 12,000 miles, while those in South Africa tend to remain closer to the coast.

Where Do Great White Sharks Migrate?

Great white sharks are found in all the world’s oceans, from the coastlines of California to the waters off South Africa, Australia, and beyond. But where exactly do great white sharks migrate to, and what are the key regions for these journeys?

Key Regions For Great White Shark Migration

Great white sharks undertake migrations to a range of regions around the world, with some of the most important areas including:

Off the coast of California, great white sharks are known to migrate to areas such as the Farallon Islands and the waters surrounding Guadalupe Island. These regions are home to large populations of seals and sea lions, which are key food sources for these predators.

South Africa

South Africa is another important region for great white shark migration, with the waters around Seal Island and Mossel Bay being particularly popular destinations. These areas are home to large populations of Cape fur seals, which are key prey items for great white sharks.

In Australia, great white sharks are known to migrate to a range of areas, including the waters off South Australia, Western Australia, and the eastern coast of the country. These migrations are often tied to the breeding and feeding behaviors of the sharks.

Other Regions

Great white sharks also undertake migrations to a range of other regions, including the waters around New Zealand, the Mediterranean Sea, and the coastlines of Japan and South America.

Migration Routes And Timing

The migration routes taken by great white sharks vary depending on the population and the factors driving the movements. For example, great white sharks in South Africa tend to move northwards during the summer months, while those in California tend to move southwards during the same season.

In general, great white sharks tend to migrate along coastlines and follow the movements of their prey. They may also follow temperature gradients in search of optimal conditions for feeding and breeding.

How Do Great White Sharks Migrate?

The migration of great white sharks is a remarkable phenomenon, involving long journeys across vast stretches of ocean. But how exactly do these predators undertake these migrations, and what adaptations allow them to do so?

Adaptations For Long-Distance Swimming

One key adaptation that allows great white sharks to migrate over long distances is their efficient swimming style. Great whites have a unique body shape that is designed for speed and maneuverability in the water, with a streamlined profile and powerful tail fin.

To conserve energy during long swims, great white sharks also use a technique known as “cruising.” This involves swimming at a constant speed without any bursts of acceleration or deceleration, which helps to reduce energy expenditure and conserve muscle glycogen stores.

Navigational Abilities

Great white sharks are also known for their impressive navigational abilities, which allow them to travel huge distances across the open ocean. While the exact mechanisms behind shark navigation are still being studied, it’s thought that they use a range of sensory cues to orient themselves.

For example, great white sharks have an acute sense of smell that allows them to detect even tiny traces of chemicals in the water. They also have a specialized sensory organ called the ampullae of Lorenzini, which allows them to sense electromagnetic fields in the ocean.

By combining these sensory inputs with visual cues such as the position of the sun and the stars, great white sharks are able to navigate with remarkable accuracy across vast stretches of ocean.

Environmental Factors

Finally, the migration of great white sharks is influenced by a range of environmental factors, including ocean temperature, prey availability, and seasonal patterns. For example, some great white shark populations migrate to warmer waters during the winter months to avoid cold temperatures, while others may move in response to changes in prey distribution.

When Do Great White Sharks Migrate?

The timing of great white shark migrations can vary depending on a range of environmental factors, as well as the specific population of sharks in question. However, there are some general patterns that have been observed in different regions around the world.

North Pacific

In the North Pacific, great white sharks are known to migrate to warmer waters during the winter months, typically between November and May. During this time, they can be found in areas such as Hawaii, California, and Baja California, where the water temperatures are more favorable for the sharks.

In South Africa, great white sharks also tend to migrate during the winter months, typically between May and September. During this time, they can be found in areas such as False Bay and Gansbaai, where they feed on seals and other prey that are abundant in the area.

In Australia, the timing of great white shark migrations can vary depending on the specific population and location. However, in general, they tend to migrate to cooler waters during the summer months, typically between December and March. During this time, they can be found in areas such as South Australia and Western Australia.

In other regions around the world, the timing of great white shark migrations can vary depending on a range of factors, including ocean temperatures, prey availability, and seasonal patterns. In some cases, sharks may undertake shorter migrations or move within a more limited range throughout the year

How Far Can Great White Sharks Migrate?

Great white sharks are capable of long-distance migrations and can travel thousands of miles in search of prey, warmer water temperatures, or breeding grounds. The farthest recorded great white shark migration was a female shark that traveled from South Africa to Australia and back, covering a distance of over 12,000 miles.

Why Do White Sharks Migrate South?

Great white sharks migrate south during the winter months to seek warmer water temperatures that are more suitable for their biology. The southward migration allows them to escape the colder waters of their summer feeding grounds and can also provide access to new prey species that are more abundant in the south.

Do Great White Sharks Migrate Alone?

Great white sharks are typically solitary animals, and there is evidence to suggest that they migrate alone rather than in groups or schools. However, researchers have observed occasional aggregations of great white sharks in areas with abundant prey, suggesting that they may come together in certain circumstances. Overall, however, great white sharks are generally considered to be solitary predators.

We have emailed you a PDF version of the article you requested.

Can't find the email?

Please check your spam or junk folder

You can also add [email protected] to your safe senders list to ensure you never miss a message from us.

How Long Does It Take For A Great White Shark To Cross An Ocean?

Complete the form below and we will email you a PDF version

Cancel and go back

IFLScience needs the contact information you provide to us to contact you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

For information on how to unsubscribe, as well as our privacy practices and commitment to protecting your privacy, check out our Privacy Policy

Complete the form below to listen to the audio version of this article

Advertisement

Subscribe today for our Weekly Newsletter in your inbox!

Fancy swimming from Africa to Australia in 99 days?

Senior Journalist

Tom is a writer in London with a Master's degree in Journalism whose editorial work covers anything from health and the environment to technology and archaeology.

Book View full profile

Book Read IFLScience Editorial Policy

Maddy Chapman

Editor & Writer

Maddy is an editor and writer at IFLScience, with a degree in biochemistry from the University of York.

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

Great white sharks migrate long distances each year, typically alone.

Image credit: Jennifer Mellon Photos/Shutterstock.com

Great white sharks are some of the world’s toughest travelers, regularly seen traversing extreme routes around the world’s oceans. They don’t gently wander on their voyages either; the iconic species can complete some of the fastest transoceanic migrations ever seen by marine animals.

In the early 2000s, a great white shark swam approximately 20,000 kilometers (12,400 miles) from South Africa to Australia then back again within nine months. The first arm of this journey eastwards across the Indian Ocean included the fastest known transoceanic return migration among marine animals, according to a 2005 study about the feat.

Researchers at the Wildlife Conservation Society named her Nicole after Australian actress Nicole Kidman (who’s apparently a huge admirer of great white sharks).

On November 7, 2003, researchers attached an electronic tracker to her dorsal fin while in the waters of South Africa. After completing the first leg of the journey, the tag fell off near Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia and relayed the data to a satellite.

It revealed that she had swum from South Africa to Australia, around 11,100 kilometers ( 6,900 miles), in just 99 days – a record-breaking feat .

The researchers thought this would be the end of the story, but she was spotted again on August 20, 2004 – all the way back in South Africa.

“This is one of the most significant discoveries about white shark ecology and suggests we might have to rewrite the life history of this powerful fish,” Dr Ramón Bonfil, a researcher at the Wildlife Conservation Society and lead author of the study, said in a statement in 2005.

“More importantly, Nicole has shown us that separate populations of great white sharks may be more directly connected than previously thought, and that wide-ranging white sharks that are nationally protected in places such as South Africa and Australia are much more vulnerable to human fishing in the open oceans than we previously thought,” explained Bonfil.

Nicole’s electronic tag revealed several other fascinating insights into shark migration . On the trip from South Africa to Australia, she swam an average of 4.7 kilometers (2.9 miles) per hour, which rivals the speed of notoriously speedy tuna.

While most of the journey was made at the ocean’s surface, Nicole regularly plunged into the Indian Ocean basin at a depth of 980 meters (3,215 feet). In 2005, this was a record breaker for great whites, but scientists have since found they can dive as deep as 1,128 meters (3,700 feet).

Great whites are undoubtedly among the greatest seafarers, but other animals complete much longer migrations via air travel. Arctic Tern, a medium-sized seabird with a super-streamlined body, travels a monumental 96,000 kilometers (60,000 miles) round trip from the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Europe to Antarctica each year.

ARTICLE POSTED IN

great white sharks,

south africa

More Nature Stories

link to article

What Happened At Chicxulub? The Asteroid Impact That Killed The Dinosaurs

Teams Of Mollusks With Little Sensors Are Used To Test The Water Quality In Warsaw

Watch Nox The Falcon Fly In The Wild Again After Surgery For Broken Wing

IFLScience We Have Questions: What's It Like Working In A Human Tissue Bank?

Take A Glimpse Into The Universe Like Never Before

Solar Storm Season, Dolphin Breath, And Resurrecting The Thylacine

- About BBC Wildlife

- Competitions

- Insects & Invertebrates

- Marine animals

- Water Plants

- Wildlife Garden

- North America

- South America

- Travel Planner

- Identify Wildlife

- How to make things

- Watch Wildlife

- Photograph Wildlife

- Photography Masterclasses

- Wildlife Gardening

- Environment

- Current issue

- Meet the team

- History of BBC Wildlife

Great white shark: your expert guide to the ocean's ultimate apex predator that can detect blood from 3 miles away

All you need to know about great white sharks, including why they are not as deadly as often feared

The great white shark is the only extant species in the genus Carcharodon and the largest predatory fish in the world.

- Incredible, hard to believe shark facts that celebrate this fascinating, yet much-maligned fish

Why are they called great white sharks?

Great white sharks belong to the family Lamnidae, which also includes porbeagle sharks, salmon sharks and mako sharks, which are the fastest shark in the ocean. A type of mackerel shark, the great white is named after its white belly.

What do great white sharks look like?

The top of its streamlined body is grey or brown in colour, mimicking the ocean depths, while its white belly matches the sunlight shining on the water’s surface, allowing it to blend in with its environment. Scientists have also discovered cells called melanocytes in the great white’s skin that appear to allow the fish to adjust its colouration, helping this predator to remain inconspicuous before it strikes from below.

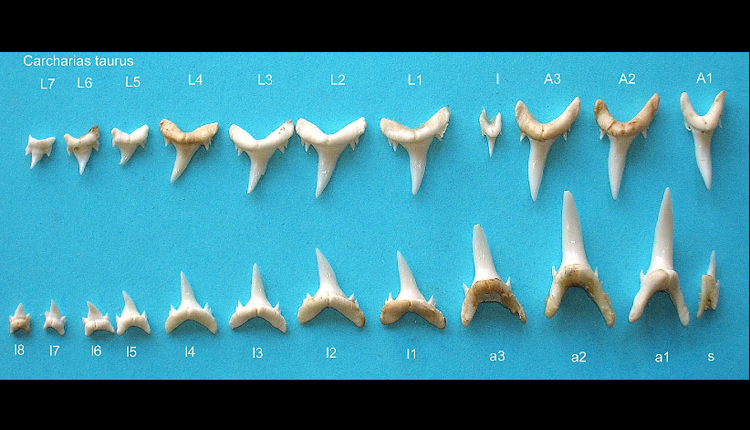

They have a large and triangular dorsal fin, a powerful lunate caudal fin, a conical snout and sharp, triangular teeth.

- How many teeth does a great white shark have? A guide to its deadly, razor-sharp gnashers

How big are great white sharks?

Great white sharks can grow to up to 6.4m in length and weigh as much as 2,041kg.

Where are great white sharks found?

Though associated with Australia and South Africa, great white sharks occur in most temperate and tropical oceans, to depths of 1,200m. They are endothermic, regulating their body temperature to allow them to swim in waters ranging from 2.7°C to 27°C. As the sharks age, their habitat preferences change: adults prefer a pelagic life while pups and young sharks tend to be found in coastal and estuary habitats.

Are there any great white sharks in UK waters?

According to the University of Plymouth, great white sharks are yet to be confirmed in UK waters, but some scientists think they might visit in future, as seas warm with climate change. Still, there have been reports since 1965, which have led to investigations by conservationist Richard Peirce. Some of the sightings were credible, but it is likely some were of the same shark.

- How many species of shark inhabit the seas around Britain?

How fast is the great white shark?

This super-swimmer can cruise for long periods of time but is also capable of high-speed pursuit, reaching about 50kph.

How does it attack?

The great white shark is an ambush hunter known for breaching (launching itself out of the water) to catch a meal in its sharp, triangular teeth, disabling its target with a bite force of up to 1.8 metric tonnes.

What do great white sharks eat?

Their diet is primarily marine mammals, including seals , dolphins and some species of whale , but they also feed on seabirds, turtles , crustaceans, molluscs and carcasses. Their young feed on smaller prey such as fish and rays .

Great white sharks travel along coastlines rich in food sources, such as seal lion rookeries. They have an acute sense of smell, detecting a colony of seals 3km away and one drop of blood in 100 litres of water.

Should humans feel threatened?

Negative portrayals of great whites as terrifying man-eaters in books and films like Jaws have had consequences for many shark species.

The Florida Museum of Natural History releases an annual international shark attack report and explains that the vast majority of unprovoked attacks are ‘test bites’, when a shark misidentifies a human as its preferred prey.

Millions of us swim in the world’s oceans each year and shark attacks remain rare. Figures for 2023 showed there were 10 fatalities caused by three species of shark: bull shark , tiger and great white.

- Steve Backshall on shark attacks: “You’re more likely to be killed taking a selfie”

How long do great white sharks live for?

Great white sharks can live for up to 73 years

How do great white sharks breed?

Females don’t reach maturity until 33 years old. The male uses claspers to internally fertilise the female, who gives birth to between two and 17 live pups.

While in utero, young may be nourished by unfertilised eggs (for protein) and ‘milk’ secreted by the female. The gestation period is estimated at 12 months with females thought to give birth in temperate shelf waters during spring to late summer, but more research is needed. Pups are born ranging from 120-165cm in length and are fully capable of hunting on their own. In January 2024, the first-ever sighting of a possible live newborn great white shark was reported in Environmental Biology of Fishes .

Do great white sharks have predators?

Great whites are apex predators in the ocean food web. However, pods of killer whales are known to hunt the species and in March 2024 the African Journal of Marine Science reported the first documented instance of an individual killer whale hunting a juvenile great white shark.

The male incapacitated his prey, before consuming its liver, and the speed of the attack surprised scientists.

- Deadliest apex predators in the wild: which ruthless mammals are the best killing machines?

- What was the first ever apex predator? Meet the prehistoric Anomalocaris who ruled before the dinosaurs

What threatens great white sharks?

The global population of great white sharks is unknown, but thought to be in decline – the species is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN. Great whites are often caught as bycatch, mostly in inshore fisheries. The sharks are also snared in beach protection nets in Australia and South Africa, but can be released. Shark fins and jaws are traded and their meat consumed or exported.

How are they being protected?

The great white is listed under several wildlife treaties, including Appendix I and II of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). “To prevent overfishing and allow recovery, it is recommended that all [great] white shark conservation commitments under international wildlife treaties be fully implemented,” says the IUCN. “[Great] white sharks should be subject to catch limits based on scientific advice and/or the precautionary approach.”

- Rarest sharks in the world: Before long many of these fascinating creatures could be extinct, warn Shark Trust

Share this article

Deputy editor, BBC Wildlife Magazine

You may also like

Discover wildlife, 10 deadliest animals to humans - discover the world's most lethal creatures, 10 deadliest fish: you won't want to meet these fearsome species underwater, 11 weirdest sharks: we take a deep dive into the ocean to discover some of its strangest creatures, 10 most incredible marine life experiences for memories that will last a lifetime.

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Code of conduct

- Subscription

- Manage preferences

New Evidence Suggests Sharks Use Earth’s Magnetic Field to Navigate

Bonnethead sharks swam in the direction of their home waters when placed in a tank charged with an electromagnetic field

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)

Correspondent

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/1e/c11e82a0-a044-4d60-a9a9-e1f32d3a6f5d/gettyimages-549035883_web.jpg)

Every December, great white sharks swimming off the coast of California make a beeline for a mysterious spot in the middle of the Pacific roughly halfway to the Hawaiian islands. The sharks travel roughly 1,000 miles to the so-called white shark cafe . Tracking data has revealed that their routes are remarkably direct considering their paths traverse apparently featureless open ocean. Tiger sharks , salmon sharks and multiple species of hammerheads also make lengthy journeys to and from precise locations year after year.

Pete Klimley, a retired shark researcher who worked at the University of California, Davis calls the ability of some animals to find their way to pinpoint locations across the globe “one of the great mysteries of the animal kingdom.”

Now, new research published today in the journal Current Biology provides new support for a longstanding hypothesis that sharks use the Earth’s magnetic field to navigate during their long-distance migrations. Scientists caught bonnethead sharks off the coast of Florida and put them in a tank surrounded by copper wires that simulated the magnetic fields sharks would experience in locations hundreds of miles from their home waters. In one key test, the bonnetheads were tricked into thinking they were south of their usual haunts and in response the sharks swam north.

Iron and other metals in Earth’s molten core produce electrical currents, which create a magnetic field that encircles the planet. The north and south poles have opposing magnetic signatures and invisible lines of magnetism arc between them. The idea that sharks can navigate by sensing these fields rests on the fact that Earth’s geomagnetism isn’t evenly distributed. For example, the planet’s magnetism is strongest near the poles. If sharks can somehow detect the subtle perturbations of Earth’s magnetic field, then they might be able to figure out which way they’re heading and even their position.

Sharks are known to have special receptors—tiny jelly-filled pits called ampullae of Lorenzini that are clustered around their noses—which can sense changes in voltage in the surrounding environment. In theory, these electroreceptors, which are usually used to detect the electrical nerve impulses of prey, could pick up Earth’s magnetic field. Prior experiments have shown that, one way or another, sharks can indeed perceive and react to magnetic fields , but figuring out whether sharks can use them to navigate long distances or as a kind of map is another matter.

To test whether sharks can use the Earth’s magnetic field to orient themselves, researchers caught 20 roughly two-foot-long bonnethead sharks off Florida’s Gulf Coast at a spot called Turkey Point Shoal . Bonnetheads are a small species of hammerhead known to travel hundreds of miles and then return to the same estuaries they were born in to breed every year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/73/6473016c-b0d0-4900-bff4-de5bad3aa4f0/this-image-shows-bryan-keller-holding-a-bonnethead-shark-credit-colby-griffiths_web.jpg)

Picking a small species was crucial, says Bryan Keller, a marine biologist at Florida State University and the study’s lead author, because he and his co-authors needed to put the sharks in a tank and then build a structure that could produce electromagnetic fields that they could manipulate horizontally as well as vertically around the sharks.

Using two-by-four lumber and many feet of copper wire rigged up to a pair of adjustable electric power supplies, the team made a roughly ten-foot-wide cube that could create magnetic fields with variable poles and intensity. This allowed the team to mimic the geomagnetic conditions of three different locations on Earth to see how each impacted the sharks’ behavior.

The three magnetic locations the sharks were exposed to consisted of the place they were caught (the control treatment), a location about 370 miles north of where they were caught (the northern scenario) and a location 370 miles south (the southern scenario) of where they were caught.

As the researchers expected, when the bonnetheads were placed amongst magnetic fields of a similar intensity and arrangement to their home range they didn’t exhibit any apparent preference for swimming in one direction over another inside their tank.

Next, the northern scenario simulated something that no shark would ever experience in the wild: the magnetic conditions of Tennessee. This test was aimed at figuring out if the sharks could orient themselves toward home in a totally unnatural geomagnetic context that they would have had no occasion to ever experience. Alas, the movements of the sharks in the northern treatment showed no statistically significant heading. Keller says this non-result wasn’t terribly surprising, since the bonnetheads would never need to find their way home from Tennessee in nature.

But in the southern scenario, in which the magnetic fields were tweaked to approximate a location about 100 miles west of Key West, the sharks tended to orient themselves northward—towards home.

“To orient towards home, these sharks must have some kind of a magnetic map sense,” says Keller. “If I put you in the middle of nowhere you couldn't point toward your house unless you knew where you were in relation to it, and that’s a map sense.”

Klimley, who was not involved in the paper and is one of the progenitors of the notion that sharks use geomagnetism to navigate , says the experiments “show that if you give sharks a magnetic environment that’s different from what the sharks have in their home range, they will head for home.”

But other researchers aren’t convinced that the word “map” is appropriate to describe the sharks’ apparent ability to orient themselves by detecting magnetic fields.

“This is a good study but what I don’t buy into is that it demonstrates the use of a magnetic map,” says James Anderson, a researcher studying sharks’ sensory systems at California State University, Long Beach who was not involved in the paper. Anderson says Keller’s study shows that bonnetheads could orient themselves toward home, but adds, “a magnetic map implies the animal knows not just where it is and where it’s going but also its end destination—for example, ‘I need to go north for 500 miles to get to seamount X.’ And I’m not sure they’ve shown that here.”

The paper also drew support for its findings regarding sharks’ magnetically-guided navigation from the genetic makeup of various subpopulations of bonnetheads scattered along the perimeter of the Gulf of Mexico and Florida’s Atlantic Coast. Keller and his co-authors calculated the genetic distance between more than ten populations of bonnetheads using samples of their DNA.

When populations are separated by some barrier like physical distance or an obstacle that prevents them from mixing and breeding with each other, genetic differences tend to accumulate over time and ultimately lead to increasingly divergent DNA.

When Keller and his co-authors looked at the bonnetheads’ mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only from the individual’s mother, the team found that physical distance and differences in temperature didn’t provide the best statistical explanation for the genetic distances they saw between populations. Instead, the populations with the greatest genetic distances between them tended to have home areas that also had very different magnetic signatures.

Because female bonnetheads return to the same estuary they were born in to give birth, and because mitochondrial DNA is only inherited from momma sharks, these results support the idea that these females’ sense of what feels like home may be partly defined by local magnetic fields.

“This highlights the possibility that females might choose pupping grounds partly based on magnetic signatures,” says Keller.

Great white shark researcher Salvador Jorgensen of the Monterey Bay Aquarium says he thinks the finding that sharks use Earth’s magnetic fields to orient and navigate is likely to apply to a majority of shark species, including the big, toothy ones he studies. “I’m intrigued by this study because we recognize the same individuals returning to the same seal rookeries on the Central California coast for 15 to 20 years with pinpoint accuracy,” says Jorgenson, who was not involved in the paper. “And that’s after travelling thousands of miles to and from the white shark cafe or Hawaii.”

Scientists’ expanding sense of how sharks perceive their environment may even one day help researchers understand if humans are blocking or confusing the animals’ navigation as offshore infrastructure continues to grow in scope and complexity.

“One of the things that makes this work important is that they’re putting in wave farms and offshore wind farms and all of these projects have big high-voltage cables leading to shore,” says Klimley. “Those cables put off their own electric fields and if that’s how sharks navigate, we need to find out how that undersea infrastructure might impact migratory sharks.”

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/alex.png)

Alex Fox | | READ MORE

Alex Fox is a freelance science journalist based in California. He has written for the New York Times, National Geographic, Science , Nature and other outlets . You can find him at Alexfoxscience.com .

Why Do Sharks Migrate? (4 Causes for Shark Migration)

Sharks migrate for various reasons, including seasonal changes, mating, feeding, and temperature changes in the water.

Some species of shark, such as the great white, migrate long distances to find warmer waters.

Many shark species are known to migrate in common with numerous land, air, and sea animals.

However, unlike land animals or birds that are comparatively easy to observe, scientists have historically been challenged to track sharks’ movements underwater.

Why do sharks migrate? Advances in satellite tagging have increased the understanding of sharks’ behavior somewhat.

Scientists believe that shark migration patterns are associated with four main causes: mating, giving birth, feeding, and in response to seasonal temperature changes.

We will answer the question “why do sharks migrate” by looking at these specific circumstances. We will also consider the most studied of all the migratory sharks, the famous great white shark.

So read on, and we will delve into this fascinating and mysterious behavior.

Table of Contents:

- 4 Causes of Shark Migration

- Do All Sharks Migrate?

- Where do Sharks Migrate to?

- How do Great White Migrate Huge Distances?

The 4 Causes of Shark Migration

Migration refers to the movement of animals from one region to another and is observed in all animal groups. However, scientists’ understanding of the specific migration mechanism (for example, how are sharks able to migrate?) remains relatively vague.

Scientists, fishermen, and scuba divers have long believed that sharks migrate when they have observed them seasonally disappearing and then reappearing at a location.

Satellite tagging data has allowed scientists to see specific animals traveling significant distances. This has cleared up some mysteries about where the sharks were disappearing to.

Reading Suggestion : Do Sharks Jump Out of the Water?

For example, although they had been observed moving, it was thought that great white sharks always stayed locally in coastal waters to feed on nearby sea lions and elephant seal populations.

However, tagging has shown that individuals often migrate over many thousands of miles.

Studies often only track a small number of individuals making hard evidence challenging to find.

More extensive studies are needed for each shark species to uncover all the mysteries of their migration. However, we can reasonably assume that the reasons why sharks migrate fall into these four categories.

1. Sharks Migrate To Mate

Some shark species are believed to migrate long distances to find a mate and reproduce. For example, sandbar sharks (Carcharhinus plumbeus) have been observed arriving to mate in significant numbers in spring off the east Florida coast.

Blue sharks (Prionace glauca), a deep water requiem shark, are thought to migrate to subtropical waters in early summer to mate before returning to more temperate waters.

Another requiem shark, the blacktip shark (Carcharhinus limbatus), is seen to migrate in their thousands to the waters close to the Florida shore every winter to mate.

The reproduction cycle of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is still largely unknown.

However, scientists have tracked tagged sharks traveling considerable distances to reach the eastern Pacific’s subtropical open ocean regions. While the reason for their visiting the sea west of Baja California is uncertain, this could be for mating

Reading Suggestion: 17 Surprising Hammerhead Shark Facts

2. Sharks Migrate To Give Birth

Once mating has taken place, it is thought that many shark species migration patterns will include a journey to give birth .

Once mating has taken place, the female sandbar sharks, for example, will move north and travel to northwestern estuaries and bays, including Delaware Bay, to give birth to their pups.

Blue sharks appear to give birth in temperate waters, and it has then been observed that juvenile females seem to move north while young males head south.

A study in the 1990’s observed that several female lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris) seemed to return about every two years to a lagoon in the Bahamas to give birth.

After carrying out an extensive study over eighteen years, genetic sampling and tagging showed that female sharks over fifteen years old were returning to the same lagoon to give birth as they had been born.

Reading Suggestion : Do Sharks Sleep?

The research demonstrated that while the adult lemon sharks weren’t seen in the lagoon at other times of the year, the females were visiting their birthplace to give birth.

Pregnant great white sharks have been tracked from their Guadalupe Island mating grounds for 24 months in the open ocean until they traveled to the sea off Baja, California, to give birth.

After the shark pups had been born, the females were then seen to return to Guadalupe Island to mate once more.

Other studies involving great white sharks have shown high numbers of juveniles in waters of the North Atlantic off the state of New York.

It is suggested that pregnant females visit the area in the summer months to give birth and that its food-rich shallow oceans make the perfect nursery.

3. Sharks Migrate to Find New Feeding Grounds

The leading cause of many animal migrations is the pursuit of suitable food sources .

For sharks, this could be following fish movements that migrate to different locations throughout the year. Oher sharks may follow the travels of marine mammals, including seals and sea lions, who move following fish and temperature changes.

Great white sharks are seen off the coast of California in locations such as Año Nuevo and the Farallon Islands in Spring, where they will feed on elephant seal pups, a nutritious high-fat food source.

The same great white shark population is thought to travel to the most northern extents of their range during the summer when they travel as far as the southern Alaskan islands on the eastern Pacific coast of the United States following the seals.

Great white sharks have been tracked over thousands of miles moving between feeding grounds. These travels to find the best food use vast amounts of energy , so this migration must result in significant amounts of food to be worthwhile.

Reading Suggestion: Can Bull Sharks live in Freshwater?

4. Sharks Migrate Because of Seasonal Changes in Temperature

Cold-blooded sharks are relatively sensitive to water temperature, and some migration patterns are thought to occur as sharks try to stay in their favored temperature range .

Some sharks’ high metabolic rate, including the great white and shortfin mako ( Isurus oxyrinchus ), allows them to generate their own heat.

This lets these sharks tolerate a much greater range of temperatures which lets them focus on traveling to lower temperatures where the food sources are prioritized over chasing heat.

Reading Suggestion : Can s Shark Drown?

Climate change seems to play its part in sharks’ temperature-related migration patterns. The tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) is being driven from its usual areas by increasing temperatures.

During particular warm periods, tiger sharks have been found in waters off the northeast coast of the United States that would have historically been too cold for them.

A research team has tracked tiger sharks migrating approximately 400 kilometers / 250 miles further north for each 1°C increase in average water temperature.

Climate change-driven movements of apex predator sharks into previously unvisited waters could significantly impact their regular fish and wildlife populations.

Are All Sharks Migratory?

No, not all sharks are migratory . Sharks consist of more than 470 species and exhibit an extensive range of different behaviors.

Some sharks are solitary and only meet for breeding or in rich hunting grounds . Others live in social groups which travel and exist together for their entire lives.

Local sharks, including nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) and some reef sharks, are considered not to migrate. This group will usually stay around the same location and only travel a maximum of about 160 kilometers / 100 miles from a central point.

Pelagic sharks, including tiger sharks , the blacktip shark, and sandbar sharks, migrate along coastal waters, following food and temperature across a distance of about 1,600 kilometers / 1,000 miles.

Species including great white sharks, blue sharks, and mako sharks are known as highly pelagic and will migrate over many thousands of miles each year.

Reading Suggestion: How Do Sharks Die?

What Season Do Sharks Migrate In?

Some sharks could be regarded as being in an almost constant state of migration as they travel from place to place for mating, reproduction, and food during their entire life history.

Others have a more predictable schedule that you can follow. The blacktip shark, for example, can be seen migrating along the eastern seaboard of the United States between North Carolina and Florida during late winter and early spring every year. Their arrival is known locally in Florida as “shark season” and is eagerly predicted.

As sharks often move due to water temperature, you can reasonably predict that many species will be seen further from the equator in warmer months and closer as it is colder.

Tagged great white sharks are seen to leave the Cape Cod area in late autumn to spend their winter in the warmer waters off the southeastern United States and in the Gulf of Mexico.

Where Do Sharks Migrate To?

When asking why do sharks migrate, many people are interested in knowing where sharks migrate to.

As we have seen, shark migration is driven by several factors, so depending on the species, their migration paths can be led by what sharks like to eat, the temperature, or where they will be able to mate and give birth.

The migration of the blacktip shark along the eastern United States coastline seems to be driven primarily by water temperature.

In fact, as water temperatures in their northern habitats have risen, some blacktip sharks have been observed to stop migrating south at all.

Great white shark migration for food can be predicted by the location of near shore habitats with large populations of suitable mammals, including seals and sea lions.

Migrations to the same areas to give birth may be down to the fact that these locations have historically produced sufficient food in safe places for a population of juvenile sharks to flourish.

How Far Do Sharks Migrate?

The distance that sharks migrate depends hugely on their species. Great white sharks have frequently been observed to migrate as far as 4,000 kilometers / 2,500 miles each year between the central California coast and the Pacific Ocean.

On the other hand, coastal pelagic sharks may only travel around a maximum of 1,600 kilometers / 1,000 miles per year for their migration.

How do Great White Sharks Migrate Such Huge Distances?

The extensive migrations of great white sharks can cause them to travel across vast distances of open ocean where food sources can be extremely scarce.

Researchers from the University of Hawaii and the Hopkins Marine Station realized that great white sharks use large supplies of fat stored in their livers to fuel their long journeys.

The liver of the great white can make up as much as a quarter of its body weight, and 90% of it is beneficial lipid fats.

In the absence of blubber-rich seals, sea lions, or whales to eat, the shark’s livers are metabolized to give them the energy to swim.

Once the shark has reached their version of an Outback Steakhouse where the sea mammals are abundant, it can refuel its livers stores.

Shark Migration Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How Far Do Great White Sharks Travel?

A: Great white sharks have been seen to have long migrations of at least 4,000 kilometers / 2,500 miles each year during their migrations.

Q: How Far Do Sharks Travel in a Day?

A: While not known for sure, it’s been estimated that great white sharks could travel at least 80 kilometers / 50 miles in a day.

Q: Do Sharks Hibernate or Migrate?

A: Sharks often migrate to warmer areas to reach their preferred water temperature. Sharks aren’t known to hibernate, but some are thought to sleep somehow.

It’s suggested that sharks who need to swim constantly to get oxygen-rich water to their gills go through periods of relaxation and activity, resting parts of their bodies while still breathing.

Q: Do Sharks Migrate in the Winter?

A: Yes, many shark species will migrate to warmer waters in the winter to stay in their preferred water temperature or seek food.

Q: How Cold Can a Shark Survive?

A: This depends on the type of shark. For example, salmon sharks (Lamna ditropis) can live in waters of just 2°C / 36°F in the North Pacific, thanks to their high metabolic rates. Great white sharks seem to enjoy waters that are no cooler than about 12°C / 53°F.

As we’ve considered why do sharks migrate, we’ve seen that it is a combination of four reasons: mating, giving birth, to find food, and following their preferred water temperature.

There’s a lot that marine sciences don’t understand about sharks’ lifecycles, including their migration patterns. As further research is carried out, we might learn more about the lives of these fascinating creatures.

Additionally, as climate change impacts their existence, we will need to understand how sharks might need to adjust their behavior to accommodate changes in ocean temperature and the location of their preferred feeding grounds. Sharks may have to migrate to new areas, affecting fish and human populations.

Reading Suggestion : Do Sharks Have Tongues?

British-born Dan has been a scuba instructor and guide in Egypt’s Red Sea since 2010.

Dan loves inspiring safe, fun, and environmentally responsible diving and particularly enjoys the opportunity to dive with sharks or investigate local shipwrecks.

When not spending time underwater, Dan can usually be found biking and hiking in Sharm’s desert surroundings.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How Far Do Great Whites Swim Each Day?

Great white sharks, also known as white sharks, white pointers, or most commonly simply great whites, are a large species of mackerel shark.

Great whites have a fearsome reputation, and are arguably the most well-known shark in the world as a result of their reputation for attacking humans.

Because they are so well-known, people have more questions about great white sharks than just about any other shark species.

One question people often ask is how far great whites swim in a day. Naturally, because great whites must continually swim in order to breathe, they can cover some impressive distances.

Obviously, no two great whites are the same, and each will swim slightly different distances each day depending on their size and swimming speed.

Nevertheless, it is thought that on average great whites swim roughly 50 miles every day.

Although they don’t swim at this speed all the time, great whites can swim at speeds of up to 25km per hour in short bursts and can dive to depths of about 3900 feet. How do great whites swim so well?

They’re perfectly designed to be excellent swimmers. They use their powerful tails to propel themselves through the water quickly and efficiently.

They also have pointed, crescent-shaped tails that help the great white to cut through the water and remain streamlined.

Why Do Great White Sharks Need To Cover Such Long Distances?

Great white sharks would be far from at home in an aquarium or sea life park. They are migratory creatures, covering massive distances each year in the hunt for new feeding grounds.

When faced with nothing but the open ocean, great white sharks have been known to travel up to 2500 miles (4000 kilometers) in one go, sometimes quite literally in a straight line.

When migrating, great whites typically stick to near the surface of the ocean.

Unfortunately for great white sharks, vast swathes of the open seas are virtually devoid of any prey to sustain them. Instead, great whites sustain themselves with a ‘backup’ source of energy.

It comes from the liver, and comes in the form of lipids. Luckily, a great white shark’s liver is absolutely huge, making up more than a quarter of the shark’s total body weight.

As great white sharks migrate, they power themselves across the seas using this stored energy reserve.

How Fast Can A Great White Swim?

As with many apex predators, the great white is at its fastest when chasing prey over short distances.

In such instances, the great white can hit a top speed of about 25 kilometers per hour, which equates to roughly 16 miles per hour.

This does, however, vary from shark to shark. Naturally, the smaller and more streamlined great white sharks can travel at greater speeds than larger sharks carrying more weight.

Having said that, great whites swim at a much more leisurely pace when migrating, as they have no need to waste precious energy, especially in an environment that has a dearth of prey.

How Far Can A Great White See, And Does This Help Them While Migrating?

If you’ve ever seen a great white’s eyes, you will know how striking they are. They are impressively large and have a deep, navy blue hue.

You might even find yourself reminded of human eyes when looking at them. Although they are five times larger than human eyes, great white eyes have a somewhat similar structure to our own.

This goes some way to explaining their highly impressive vision.

So what are great white eyes like? The retina has two constituent parts, each with its own adaptation.

One part is designed for dealing with daylight, whilst the other part is adapted to deal with nighttime and the poor light conditions of deeper waters. As previously mentioned, the iris itself is a dark shade of navy blue.

One interesting adaptation that great whites have in terms of eyesight is their tendency to roll their eyes back into the socket in moments of danger, particularly when hunting prey.

In terms of hunting, another adaptation that great whites have is a layer of reflective crystals at the back of each eye socket.

These have the ability to detect even the slightest bit of movement from potential prey, and tell the shark exactly which direction it is coming from.

With such helpful adaptations, a great white can see for distances of up to 820 feet, which is about 250 meters away.

Such sharp vision is of course helpful whilst traveling across the ocean waves, and they can see their destination long before they actually reach it.

How Does A Great White Sustain Itself Over Long Distances?

As we discussed earlier, large swathes of the ocean are lacking in the kind of prey that a great white normally eats to sustain itself.

Consequently, great whites power their migrations with lipids stored in their huge livers. They build up this lipid store by eating large amounts when they are not migrating.

So what do great whites eat? Well, young great white sharks eat mostly small prey, like rays and fish.

Fully grown great whites, on the other hand, tend to go for much larger prey like seals, sea lions, sea turtles, and even some smaller species of whale.

Great whites are also, to a degree, scavengers, and will feed on any dead creatures they come across in the water.

Great whites eat a lot of this prey, too, eating up to 11 tonnes worth of meat in a single year.

Sharks usually subdue their prey by attacking quickly and forcefully, hoping to inflict massive wounds that will either force the prey into shock or lead it to bleed to death a short time later.

When the creature does bleed out, the shark then simply follows the smell of blood and returns to feast on its carcass.

Another adaptation that great whites have that helps them to hunt their prey is the presence of ampullae. These two ‘sensors’ in the skull detect electrical pulses, which the great can use to detect the thrashing of wounded prey.

Of course, it would be remiss of us to talk about great whites without mentioning their teeth. Their massive teeth, of ‘Jaws’ fame, are triangular and feature serrated edges for slicing through flesh.

A great white has literally dozens of teeth, with rows of replacement teeth further behind.

You can see why a great white would need replacement teeth, as their teeth go through a large amount of wear and tear and are prone to breaking.

When older teeth break, there are always newer ones waiting in the wings to take their place. In fact, a great white can have over 300 teeth.

Unlike humans, great whites don’t have to brush their teeth.

Each tooth has a cavity-resistant fluoride coating, and its enamel contains a chemical known as fluorapatite which is naturally resistant to the acid produced by bacteria build-up.

Do Great Whites Often Travel Long Distances?

Yes, great whites regularly travel long distances. They are, for starters, an inherently migratory species. On top of this, great whites get their oxygen from a technique called ‘ram ventilation’.

This means that the shark needs to swim constantly in order to breathe, as it is the act of swimming itself that forces water across the gills.

Therefore, they can never stop swimming, so they naturally cover long distances. This is unlike other species of fish, that have more complex systems to pump water into and out of the gills.

Great whites, although migratory and often solitary, still have a bunch of social and behavioral systems.

Female great whites, larger than their male counterparts, tend to dominate, whilst sharks resident in a given area will also dominate sharks that have only recently arrived.

One way that great white sharks display their dominance is with a bite. The best way to describe the social structure of great white sharks is probably as ‘like a wolf pack’.

They mostly live peacefully in a group, although there is a clear hierarchy and each group has a ‘top shark’ that leads as an alpa.

Great Whites are more intelligent and naturally curious than many people give them credit for, and they need this intelligence in order to relate to other sharks.

Interestingly, great whites are one of only a few shark species that ever exits the water.

Despite weighing in at 2000lbs or more, great whites on the hunt for fast-moving prey like seals are known to launch themselves up to 10 feet into the air in a process known as ‘breaching’.

Why Are They Called White Sharks?

Great whites are, as the name suggests, largely white in appearance. Well, at least the underside is. Their top side is a darker, gray color. This coloring functions as a camouflage.

From below, the white underside of the shark blends in with the bright rays of sun coming from above. From above, the dark gray blends in well with the deeper and darker depths of the ocean below them.

Can Great White Sharks Survive In Freshwater?

No, great whites can’t survive for any length of time in freshwater, as they are adapted to the saltwater environment of the sea.

In fact, a shark’s body needs salt in order to function. Without it, their cells will begin to rupture and their bodily functions will begin to fail. The result, soon after, would be the great white’s death.

That’s without even mentioning the fact that sharks don’t have a swim bladder for buoyancy.

As freshwater is less buoyant than saltwater, the great white would have serious problems keeping itself afloat in freshwater. In fact, it would be 2 or 3 times less buoyant.

Final Thoughts

Estimates suggest that great white sharks can travel up to about 50 miles a day. They need to be able to travel so far for two reasons.

Firstly, to migrate to new hunting grounds where food is more plentiful. Secondly, as ram ventilators, great whites need to be constantly on the move in order to breathe.

- Recent Posts

- Is It Possible For A Shark To Swim Backwards? - August 2, 2022

- Are Leopard Sharks Dangerous? - August 2, 2022

- What Are The Differences Between Shark And Dolphin Fins? - August 1, 2022

Related Posts:

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Great white sharks: The world's largest predatory fish

Great white sharks are anything but mindless killers.

Conservation status

Additional resources, bibliography.

Great white sharks , ( Carcharodon carcharias ), also known as white sharks, are the largest predatory fish in the world. They belong to a partially "warm-blooded" family of sharks called Lamnidae, or mackerel sharks, that are able to maintain an internal body temperature that's warmer than their external environment — unlike other "cold-blooded" sharks, which can't, according to the Florida Museum of Natural History .

Great white sharks are the only living members of the genus Carcharodon — inspired by the Greek words "karcharos," which means sharpen, and "odous," which means teeth. This name is well-chosen, as great white sharks have rows of up to 300 serrated, triangular teeth. These sharks have bullet-shaped bodies, gray skin and white bellies.

Despite being one of the best-known shark species thanks to movies such as "Jaws" (1975), great white sharks live a secretive lifestyle, and scientists still have much to learn about these iconic predators.

How big are great white sharks?

Great white shark size varies, but females can grow to be larger than males. Female great white sharks reach an average length of 15 to 16 feet (4.6 to 4.9 meters), while males usually reach 11 to 13 feet (3.4 to 4 m), according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. The largest great white sharks can grow to 20 feet long (6.1 m), and there are unconfirmed reports of great whites growing to 23 feet long (7 m), according to the Florida Museum of Natural History . Adults weigh between 4,000 and 7,000 pounds (1,800 and 3,000 kilograms), according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

Great whites are not the biggest sharks in the world. That title goes to whale sharks ( Rhincodon typus ), which are filter-feeders and usually grow up to 33 feet (10 m) long and weigh around 42,000 pounds (19,000 kg). The biggest shark species ever was the now-extinct megalodon ( Carcharocles megalodon ), which may have grown up to 60 feet long (18 m) or more, although scientists are still debating its exact size.

Related: Scientists discover great white shark 'queen of the ocean'

Where do great white sharks live?

Great white sharks have a large geographic range; they live in most temperate and tropical oceans around the world and have resident populations off the coasts of the U.S., Australia, South Africa and other countries. They are most often sighted in cooler, temperate waters and swim at the surface as well as down to more than 3,900 feet (1,200 m) below the surface, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Chondrichthyes

Order: Lamniformes

Family: Lamnidae

Genus & species: Carcharodon carcharias

Source: ITIS

Great white sharks are migratory and undertake long-distance journeys across the open ocean, possibly for food and breeding. A 2002 study published in the journal Nature found that one great white shark swam 2,360 miles (3,800 kilometers) from the coast of central California to the Hawaiian island of Kahoolawe. In 2005, researchers tracked a great white shark swimming almost 6,900 miles (11,100 km) from the coast of South Africa to Australia, before later heading back again, Mongabay reported . To have enough energy for such long journeys, great white sharks store energy in their oil-rich livers, according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium .

Related: Great white shark population off California's coast is growing

Are great white sharks dangerous?

Shark attacks are extremely rare. In 2022, just 41 shark bites were reported in the U.S., and just one was fatal. In fact, the majestic beasts actually have almost no interest in eating humans , a 2023 study found.

In fact, when researchers flew drones over the beaches of Southern California, they found juvenile sharks tended to congregate in areas heavily used by people. Yet they harmlessly swimming alongside surfers, paddleboarders and swimmers and only one unofficial shark attack was reported from these locations.

“I think what we've finally done is put a nail in the coffin for the old myth that if you're in the water with a white shark, it's going to attack you,” study co-author Chris Lowe , a marine biologist at California State University, Long Beach, previously told Live Science.

When sharks do bite humans, it's likely to be a mistake. A 2021 study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface found that to a juvenile great white shark, the shape and motion of humans swimming or paddling on surfboards looks the same as seals — one of their main sources of food. This suggests attacks could be a case of mistaken identity, at least for juveniles.

"White sharks are often portrayed as 'mindless killers' and 'fond of human flesh,' however, this does not seem to be the case, we just look like their food," Laura Ryan, lead author of the 2021 study and a postdoctoral researcher at Macquarie University in Australia, previously told Live Science .