What Was the Age of Exploration?

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

The Birth of the Age of Exploration

The discovery of the new world, opening the americas, the end of the era, contributions to science, long-term impact.

- M.A., Geography, California State University - East Bay

- B.A., English and Geography, California State University - Sacramento

The era known as the Age of Exploration, sometimes called the Age of Discovery, officially began in the early 15th century and lasted through the 17th century. The period is characterized as a time when Europeans began exploring the world by sea in search of new trading routes, wealth, and knowledge.

During this era, explorers learned more about areas such as Africa and the Americas and brought that knowledge back to Europe. Massive wealth accrued to European colonizers due to trade in goods, spices, and precious metals. Nevertheless, there were also vast consequences. Labor became increasingly important to support the massive plantations in the New World, leading to the trade of enslaved people, which lasted for 300 years and had an enormous impact on Africa and North America.

The impact of the Age of Exploration would permanently alter the world and transform geography into the modern science it is today.

Key Takeaways

- During the Age of Exploration, methods of navigation and mapping improved, switching from traditional portolan charts to the world's first nautical maps; the colonies and Europe also exchanged new food, plants, and animals.

- The Age of Exploration also decimated indigenous communities due to the combined impact of disease, overwork, and massacres.

- The impact persists today, with many of the world's former colonies still considered the developing world, while colonizing countries are the First World countries, holding a majority of the world's wealth and annual income.

Many nations were looking for goods such as silver and gold, but one of the biggest reasons for exploration was the desire to find a new route for the spice and silk trades.

When the Ottoman Empire took control of Constantinople in 1453, it blocked European access to the area, severely limiting trade. In addition, it also blocked access to North Africa and the Red Sea, two very important trade routes to the Far East.

The first of the journeys associated with the Age of Discovery were conducted by the Portuguese. Although the Portuguese, Spanish, Italians, and others had been plying the Mediterranean for generations, most sailors kept well within sight of land or traveled known routes between ports. Prince Henry the Navigator changed that, encouraging explorers to sail beyond the mapped routes and discover new trade routes to West Africa.

Portuguese explorers discovered the Madeira Islands in 1419 and the Azores in 1427. Over the coming decades, they would push farther south along the African coast, reaching the coast of present-day Senegal by the 1440s and the Cape of Good Hope by 1490. Less than a decade later, in 1498, Vasco da Gama would follow this route to India.

While the Portuguese were opening new sea routes along Africa, the Spanish also dreamed of finding new trade routes to the Far East. Christopher Columbus , an Italian working for the Spanish monarchy, made his first journey in 1492. Instead of reaching India, Columbus found the island of San Salvador in what is known today as the Bahamas. He also explored the island of Hispaniola, home of modern-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Columbus would lead three more voyages to the Caribbean, exploring parts of Cuba and the Central American coast. The Portuguese also reached the New World when explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral explored Brazil, setting off a conflict between Spain and Portugal over the newly claimed lands. As a result, the Treaty of Tordesillas officially divided the world in half in 1494.

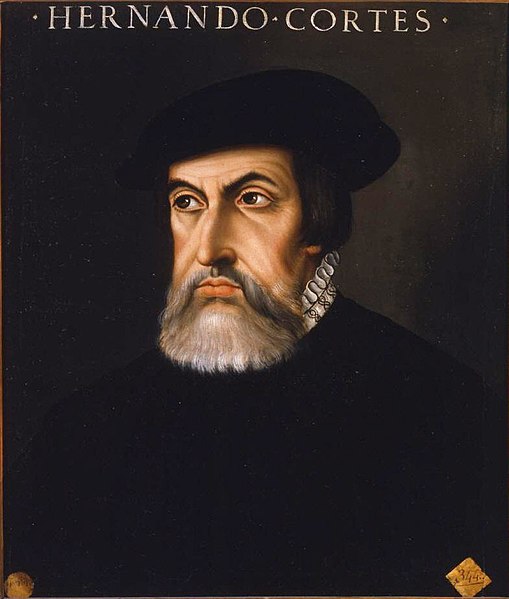

Columbus' journeys opened the door for the Spanish conquest of the Americas. During the next century, men such as Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro would decimate the Aztecs of Mexico, the Incas of Peru, and other indigenous peoples of the Americas. By the end of the Age of Exploration, Spain would rule from the Southwestern United States to the southernmost reaches of Chile and Argentina.

Great Britain and France also began seeking new trade routes and lands across the ocean. In 1497, John Cabot , an Italian explorer working for the English, reached what is believed to be the coast of Newfoundland. Many French and English explorers followed, including Giovanni da Verrazano, who discovered the entrance to the Hudson River in 1524, and Henry Hudson, who mapped the island of Manhattan first in 1609.

Over the next decades, the French, Dutch, and British would all vie for dominance. England established the first permanent colony in North America at Jamestown, Va., in 1607. Samuel du Champlain founded Quebec City in 1608, and Holland established a trading outpost in present-day New York City in 1624.

Other important voyages of exploration during this era included Ferdinand Magellan's attempted circumnavigation of the globe, the search for a trade route to Asia through the Northwest Passage , and Captain James Cook's voyages that allowed him to map various areas and travel as far as Alaska.

The Age of Exploration ended in the early 17th century after technological advancements and increased knowledge of the world allowed Europeans to travel easily across the globe by sea. The creation of permanent settlements and colonies created a network of communication and trade, therefore ending the need to search for new routes.

It is important to note that exploration did not cease entirely at this time. Eastern Australia was not officially claimed for Britain by Capt. James Cook until 1770, while much of the Arctic and Antarctic were not explored until the 20th century. Much of Africa also was unexplored by Westerners until the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The Age of Exploration had a significant impact on geography. By traveling to different regions around the globe, explorers were able to learn more about areas such as Africa and the Americas and bring that knowledge back to Europe.

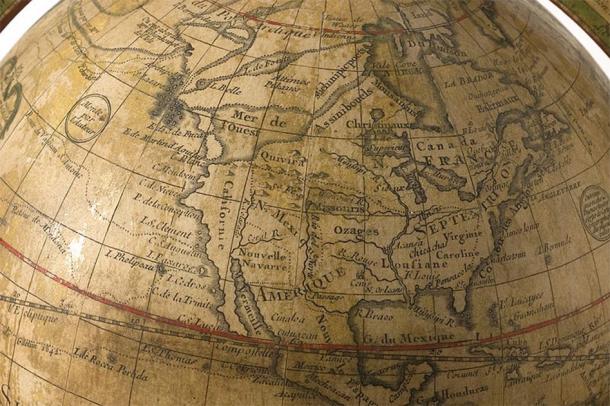

Methods of navigation and mapping improved as a result of the travels of people such as Prince Henry the Navigator. Before his expeditions, navigators had used traditional portolan charts, which were based on coastlines and ports of call, keeping sailors close to shore.

The Spanish and Portuguese explorers who journeyed into the unknown created the world's first nautical maps, delineating not just the geography of the lands they found but also the seaward routes and ocean currents that led them there. As technology advanced and known territory expanded, maps and mapmaking became more and more sophisticated.

These explorations also introduced a whole new world of flora and fauna to Europeans. Corn, now a staple of much of the world's diet, was unknown to Westerners until the time of the Spanish conquest, as were sweet potatoes and peanuts. Likewise, Europeans had never seen turkeys, llamas, or squirrels before setting foot in the Americas.

The Age of Exploration served as a stepping stone for geographic knowledge. It allowed more people to see and study various areas around the world, which increased geographic study, giving us the basis for much of the knowledge we have today.

The effects of colonization persist as well, with many of the world's former colonies still considered the developing world and the colonizing nations the First World countries, which hold a majority of the world's wealth and receive a majority of its annual income.

- Profile of Prince Henry the Navigator

- The History of Cartography

- The Rise of Islamic Geography in the Middle Ages

- Brief History and Geography of Tibet

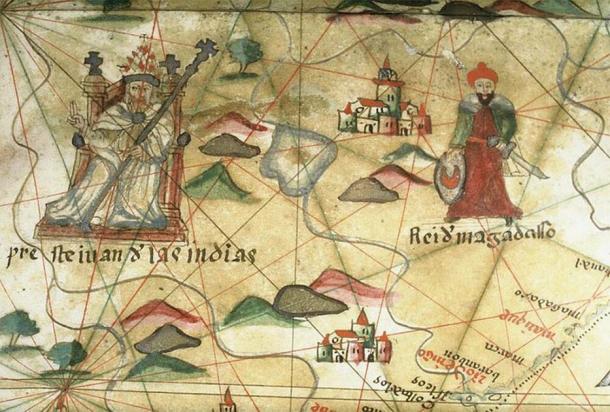

- Prester John

- Biography of Robert Cavelier de la Salle, French Explorer

- Istanbul Was Once Constantinople

- Captain James Cook

- Biography of Explorer Cheng Ho

- Ellen Churchill Semple

- Biography of Ferdinand Magellan, Explorer Circumnavigated the Earth

- Carl Ritter

- 18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

- What Is Mackinder's Heartland Theory?

- Biography of Abraham Ortelius, Flemish Cartographer

- Important Cities in Black History

The Ages of Exploration

Age of discovery, age of discovery.

15th century to the early 17th century

The Age of Discovery refers to a period in European history in which several extensive overseas exploration journeys took place. Religion, scientific and cultural curiosity, economics, imperial dominance, and riches were all reasons behind this transformative age. The search for a westward trade route to Asia was one of the largest motivations for many of these voyages. Christopher Columbus’ voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in 1492 lead to the discovery of a New World, and created a new surge in exploration and colonization. World maps changed as European powers such as England, France, Spain, the Dutch, and Portugal began claiming lands. But there were also negative effects to the Europeans’ arrival in the New World. Europeans encountered, and in many cases conquered and enslaved, native peoples of the new lands to which they traveled.

Advancements in ships, navigational instruments, and knowledge of world geography grew significantly. Vessels of the Age of Discovery continued to be built of wood and powered by sail or oar, and, on occasion, both. Medieval navigational tools such as the compass, kamal, astrolabe, cross-staff, and the mariner’s quadrant were still used but became replaced by more effective tools. Newer tools such as the mariner’s astrolabe, traverse board, and back staff soon provided better navigational support in determining longitude and latitude. These tools, along with improved maps enabled explorers to travel the vast oceans as never before. The Age of Discovery created a new period of global interaction, and began a new age of European colonialism that would intensify over the next several centuries.

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- Bibliography

The Age of Enlightenment

The age of discovery, europe’s early trade links.

A prelude to the Age of Discovery was a series of European land expeditions across Eurasia in the late Middle Ages. These expeditions were undertaken by a number of explorers, including Marco Polo, who left behind a detailed and inspiring record of his travels across Asia.

Learning Objectives

Understand the exploration of Eurasia in the Middle Ages by Marco Polo, and why it was a prelude to the advent of the Age of Discovery in the 15th Century

Key Takeaways

- European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends.

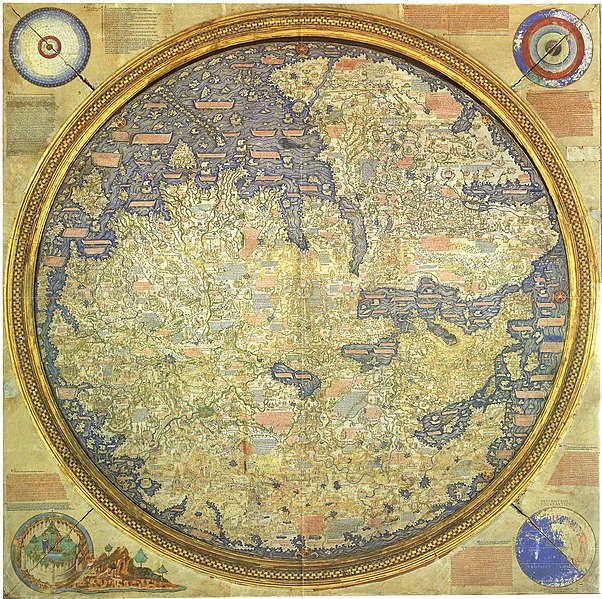

- In 1154, Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created what would be known as the Tabula Rogeriana — a description of the world and world map. It contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries.

- Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor of Ming China sponsored a series of long range tributary missions. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand.

- A series of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages marked a prelude to the Age of Discovery. Although the Mongols had threatened Europe with pillage and destruction, Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching from the Middle East to China.

- Christian embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of Syria. The first of these travelers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who journeyed to Mongolia and back from 1241 to 1247. Others traveled to various regions of Asia between 13th and the third quarter of the 15th centuries; these travelers included Russian Yaroslav of Vladimir and his sons Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, Moroccan Ibn Battuta, and Italian Niccolò de’ Conti.

- Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295. Although he was not the first European to reach China, he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. The book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers in the following Age of Discovery.

- Tabula Rogeriana : A book containing a description of the world and world map created by the Arab geographer, Muhammad al-Idrisi, in 1154. Written in Arabic, it is divided into seven climate zones and contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. The map is oriented with the North at the bottom. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries.

- Pax Mongolica : A historiographical term, modeled after the original phrase Pax Romana, which describes the stabilizing effects of the conquests of the Mongol Empire on the social, cultural, and economic life of the inhabitants of the vast Eurasian territory that the Mongols conquered in the 13th and 14th centuries. The term is used to describe the eased communication and commerce that the unified administration helped to create, and the period of relative peace that followed the Mongols’ vast conquests.

- Maritime republics : City-states that flourished in Italy and across the Mediterranean. From the 10th to the 13th centuries, they built fleets of ships both for their own protection and to support extensive trade networks across the Mediterranean, giving them an essential role in the Crusades.

European medieval knowledge about Asia beyond the reach of Byzantine Empire was sourced in partial reports, often obscured by legends, dating back from the time of the conquests of Alexander the Great and his successors. In 1154, Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi created what would be known as the Tabula Rogeriana at the court of King Roger II of Sicily. The book, written in Arabic, is a description of the world and world map. It is divided into seven climate zones and contains maps showing the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only the northern part of the African continent. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries, but it also demonstrated that Africa was only partially known to either Christians, Genoese and Venetians, or the Arab seamen, and its southern extent was unknown. Knowledge about the Atlantic African coast was fragmented, and derived mainly from old Greek and Roman maps based on Carthaginian knowledge, including the time of Roman exploration of Mauritania. The Red Sea was barely known and only trade links with the Maritime republics, the Republic of Venice especially, fostered collection of accurate maritime knowledge.

Indian Ocean trade routes were sailed by Arab traders. Between 1405 and 1421, the Yongle Emperor of Ming China sponsored a series of long-range tributary missions. The fleets visited Arabia, East Africa, India, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Thailand. But the journeys, reported by Ma Huan, a Muslim voyager and translator, were halted abruptly after the emperor’s death, and were not followed up, as the Chinese Ming Dynasty retreated in the haijin , a policy of isolationism, having limited maritime trade.

Prelude to the Age of Discovery

A series of European expeditions crossing Eurasia by land in the late Middle Ages marked a prelude to the Age of Discovery. Although the Mongols had threatened Europe with pillage and destruction, Mongol states also unified much of Eurasia and, from 1206 on, the Pax Mongolica allowed safe trade routes and communication lines stretching from the Middle East to China. A series of Europeans took advantage of these in order to explore eastward. Most were Italians, as trade between Europe and the Middle East was controlled mainly by the Maritime republics.

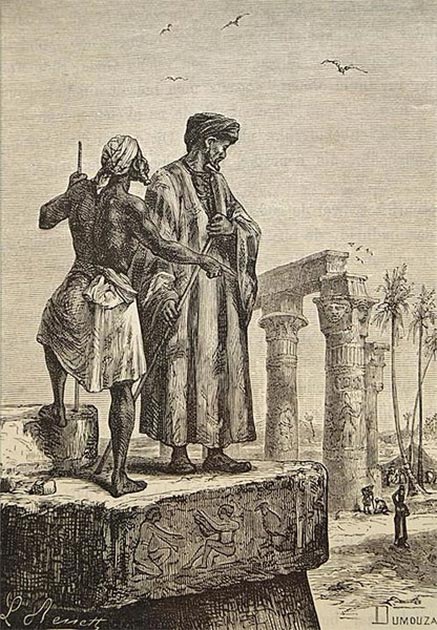

Christian embassies were sent as far as Karakorum during the Mongol invasions of Syria, from which they gained a greater understanding of the world. The first of these travelers was Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, who journeyed to Mongolia and back from 1241 to 1247. About the same time, Russian prince Yaroslav of Vladimir, and subsequently his sons, Alexander Nevsky and Andrey II of Vladimir, traveled to the Mongolian capital. Though having strong political implications, their journeys left no detailed accounts. Other travelers followed, like French André de Longjumeau and Flemish William of Rubruck, who reached China through Central Asia. From 1325 to 1354, a Moroccan scholar from Tangier, Ibn Battuta, journeyed through North Africa, the Sahara desert, West Africa, Southern Europe, Eastern Europe, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, having reached China. In 1439, Niccolò de’ Conti published an account of his travels as a Muslim merchant to India and Southeast Asia and, later in 1466-1472, Russian merchant Afanasy Nikitin of Tver travelled to India.

Marco Polo, a Venetian merchant, dictated an account of journeys throughout Asia from 1271 to 1295. His travels are recorded in Book of the Marvels of the World , (also known as The Travels of Marco Polo , c. 1300), a book which did much to introduce Europeans to Central Asia and China. Marco Polo was not the first European to reach China, but he was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. The book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travelers.

The Travels of Marco Polo : Marco Polo traveling, miniature from the book The Travels of Marco Polo ( Il milione ), originally published during Polo’s lifetime (c. 1254-January 8, 1324), but frequently reprinted and translated.

The geographical exploration of the late Middle Ages eventually led to what today is known as the Age of Discovery: a loosely defined European historical period, from the 15th century to the 18th century, that witnessed extensive overseas exploration emerge as a powerful factor in European culture and globalization. Many lands previously unknown to Europeans were discovered during this period, though most were already inhabited, and, from the perspective of non-Europeans, the period was not one of discovery, but one of invasion and the arrival of settlers from a previously unknown continent. Global exploration started with the successful Portuguese travels to the Atlantic archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores, the coast of Africa, and the sea route to India in 1498; and, on behalf of the Crown of Castile (Spain), the trans-Atlantic Voyages of Christopher Columbus between 1492 and 1502, as well as the first circumnavigation of the globe in 1519-1522. These discoveries led to numerous naval expeditions across the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans, and land expeditions in the Americas, Asia, Africa, and Australia that continued into the late 19th century, and ended with the exploration of the polar regions in the 20th century.

Portuguese Explorers

During the 15th and 16th centuries, Portuguese explorers were at the forefront of European overseas exploration, which led them to reach India, establish multiple trading posts in Asia and Africa, and settle what would become Brazil, creating one of the most powerful empires.

Compare the Portuguese Atlantic explorations from 1415-1488 with the Indian Exploration, led by Vasco da Gama from 1497-1542

- Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European overseas exploration, discovering and mapping the coasts of Africa, Asia, and Brazil. As early as 1317, King Denis made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha, laying the basis for the Portuguese Navy and the establishment of a powerful Genoese merchant community in Portugal.

- In 1415, the city of Ceuta was occupied by the Portuguese in an effort to control navigation of the African coast. Henry the Navigator, aware of profit possibilities in the Saharan trade routes, invested in sponsoring voyages that, within two decades of exploration, allowed Portuguese ships to bypass the Sahara.

- The Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama, who reached Calicut in western India in 1498, becoming the first European to reach India.

- The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast— the territory that he recommended Portugal settle.

- Portugal’s purpose in the Indian Ocean was to ensure the monopoly of the spice trade. Taking advantage of the rivalries that pitted Hindus against Muslims, the Portuguese established several forts and trading posts between 1500 and 1510.

- Portugal established trading ports at far-flung locations like Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the Maluku Islands, Macau, and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, it dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan.

- Vasco da Gama : A Portuguese explorer and one of the most famous and celebrated explorers from the Age of Discovery; the first European to reach India by sea.

- Cape of Good Hope : A rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula, South Africa, named because of the great optimism engendered by the opening of a sea route to India and the East.

Introduction

Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European overseas exploration, discovering and mapping the coasts of Africa, Asia, and Brazil. As early as 1317, King Denis made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Pesagno), appointing him first Admiral with trade privileges with his homeland, in return for twenty war ships and crews, with the goal of defending the country against Muslim pirate raids. This created the basis for the Portuguese Navy and the establishment of a Genoese merchant community in Portugal.

In the second half of the 14th century, outbreaks of bubonic plague led to severe depopulation; the economy was extremely localized in a few towns, unemployment rose, and migration led to agricultural land abandonment. Only the sea offered alternatives, with most people settling in fishing and trading in coastal areas. Between 1325-1357, Afonso IV of Portugal granted public funding to raise a proper commercial fleet, and ordered the first maritime explorations, with the help of Genoese, under command of admiral Pessanha. In 1341, the Canary Islands, already known to Genoese, were officially explored under the patronage of the Portuguese king, but in 1344, Castile disputed them, further propelling the Portuguese navy efforts.

Atlantic Exploration

In 1415, the city of Ceuta (north coast of Africa) was occupied by the Portuguese aiming to control navigation of the African coast. Young Prince Henry the Navigator was there and became aware of profit possibilities in the Saharan trade routes. He invested in sponsoring voyages down the coast of Mauritania, gathering a group of merchants, shipowners, stakeholders, and participants interested in the sea lanes.

Henry the Navigator took the lead role in encouraging Portuguese maritime exploration, until his death in 1460. At the time, Europeans did not know what lay beyond Cape Bojador on the African coast. In 1419, two of Henry’s captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, were driven by a storm to Madeira, an uninhabited island off the coast of Africa, which had probably been known to Europeans since the 14th century. In 1420, Zarco and Teixeira returned with Bartolomeu Perestrelo and began Portuguese settlement of the islands. A Portuguese attempt to capture Grand Canary, one of the nearby Canary Islands, which had been partially settled by Spaniards in 1402, was unsuccessful and met with protests from Castile. Around the same time, the Portuguese began to explore the North African coast. Diogo Silves reached the Azores island of Santa Maria in 1427, and in the following years, Portuguese discovered and settled the rest of the Azores. Within two decades of exploration, Portuguese ships bypassed the Sahara.

In 1443, Prince Pedro, Henry’s brother, granted him the monopoly of navigation, war, and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador. Later, this monopoly would be enforced by two Papal bulls (1452 and 1455), giving Portugal the trade monopoly for the newly appropriated territories, laying the foundations for the Portuguese empire.

India and Brazil

The long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama. His squadron left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut in western India in May 1498. Reaching the legendary Indian spice routes unopposed helped the Portuguese improve their economy that, until Gama, was mainly based on trades along Northern and coastal West Africa. These spices were at first mostly pepper and cinnamon, but soon included other products, all new to Europe. This led to a commercial monopoly for several decades.

The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral. While following the same south-westerly route as Gama across the Atlantic Ocean, Cabral made landfall on the Brazilian coast. This was probably an accident but it has been speculated that the Portuguese knew of Brazil’s existence. Cabral recommended to the Portuguese king that the land be settled, and two follow-up voyages were sent in 1501 and 1503. The land was found to be abundant in pau-brasil , or brazilwood, from which it later inherited its name, but the failure to find gold or silver meant that for the time being Portuguese efforts were concentrated on India.

Gama’s voyage was significant and paved the way for the Portuguese to establish a long-lasting colonial empire in Asia. The route meant that the Portuguese would not need to cross the highly disputed Mediterranean, or the dangerous Arabian Peninsula, and that the entire voyage would be made by sea.

First Voyage of Vasco da Gama: The route followed in Vasco da Gama’s first voyage (1497-1499). Gama’s squadron left Portugal in 1497, rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of East Africa. They reached Calicut in western India in May 1498.

Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia Explorations

The aim of Portugal in the Indian Ocean was to ensure the monopoly of the spice trade. Taking advantage of the rivalries that pitted Hindus against Muslims, the Portuguese established several forts and trading posts between 1500 and 1510. After the victorious sea Battle of Diu, Turks and Egyptians withdrew their navies from India, setting the Portuguese trade dominance for almost a century, and greatly contributing to the growth of the Portuguese Empire. It also marked the beginning of the European colonial dominance in Asia. A second Battle of Diu in 1538 ended Ottoman ambitions in India, and confirmed Portuguese hegemony in the Indian Ocean.

In 1511, Albuquerque sailed to Malacca in Malaysia, the most important eastern point in the trade network, where Malay met Gujarati, Chinese, Japanese, Javan, Bengali, Persian, and Arabic traders. The port of Malacca became the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia. Eventually, the Portuguese Empire expanded into the Persian Gulf as Portugal contested control of the spice trade with the Ottoman Empire. In a shifting series of alliances, the Portuguese dominated much of the southern Persian Gulf for the next hundred years.

A Portuguese explorer funded by the Spanish Crown, Ferdinand Magellan, organized the Castilian (Spanish) expedition to the East Indies from 1519 to 1522. Selected by King Charles I of Spain to search for a westward route to the Maluku Islands (the “Spice Islands,” today’s Indonesia), he headed south through the Atlantic Ocean to Patagonia, passing through the Strait of Magellan into a body of water he named the “peaceful sea” (the modern Pacific Ocean). Despite a series of storms and mutinies, the expedition reached the Spice Islands in 1521, and returned home via the Indian Ocean to complete the first circuit of the globe.

In 1525, after Magellan’s expedition, Spain, under Charles V, sent an expedition to colonize the Maluku islands. García Jofre de Loaísa reached the islands and the conflict with the Portuguese was inevitable, starting nearly a decade of skirmishes. An agreement was reached only with the Treaty of Zaragoza (1529), attributing the Maluku to Portugal, and the Philippines to Spain.

Portugal established trading ports at far-flung locations like Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the Maluku Islands, Macau, and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, it dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, China, and Japan. Jesuit missionaries followed the Portuguese to spread Roman Catholic Christianity to Asia, with mixed success.

How Portugal became the first global sea power : Pick your adjective for the monster wave McNamara rode in January just off the Portuguese coast near Nazare. The Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, came to Nazare, too, to pray before he set out in 1497—and again after a successful return from his voyage to find a sea route to India with its rich spice trade. He did what Christopher Columbus had tried to do but failed. Casimiro said that as a country, Portugal turns to the sea: “Our backs are turned to the land, and we are always looking at the sea. We have that kind of impulse to see what is after that.” Even if it’s frightening? “Yeah.” Portugal is a country where the sea is and always has been regarded as a living being—to be stared down, confronted.

Spanish Exploration

The voyages of Christopher Columbus initiated the European exploration and colonization of the American continents that eventually turned Spain into the most powerful European empire.

Outline the successes and failures of Christopher Columbus during his four voyages to the Americas

- Only late in the 15th century did an emerging modern Spain become fully committed to the search for new trade routes overseas. In 1492, Christopher Columbus ‘s expedition was funded in the hope of bypassing Portugal’s monopoly on west African sea routes, to reach “the Indies.”

- On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships. Land was sighted on October 12, 1492 and Columbus called the island (now The Bahamas) San Salvador, in what he thought to be the “West Indies.” Following the first American voyage, Columbus made three more.

- A division of influence became necessary to avoid conflict between the Spanish and Portuguese. An agreement was reached in 1494, with the Treaty of Tordesillas dividing the world between the two powers.

- After Columbus, the Spanish colonization of the Americas was led by a series of soldier-explorers, called conquistadors. The Spanish forces, in addition to significant armament and equestrian advantages, exploited the rivalries between competing indigenous peoples, tribes, and nations.

- One of the most accomplished conquistadors was Hernán Cortés, who achieved the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Of equal importance was the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire under Francisco Pizarro.

- In 1565, the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Philippines was founded, which added a critical Asian post to the empire. The Manilla Galleons shipped goods from all over Asia, across the Pacific to Acapulco on the coast of Mexico.

- reconquista : A period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula, spanning approximately 770 years, between the initial Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the 710s, and the fall of the Emirate of Granada, the last Islamic state on the peninsula, to expanding Christian kingdoms in 1492.

- Treaty of Zaragoza : A 1529 peace treaty between the Spanish Crown and Portugal that defined the areas of Castilian (Spanish) and Portuguese influence in Asia to resolve the “Moluccas issue,” when both kingdoms claimed the Moluccas islands for themselves, considering it within their exploration area established by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. The conflict sprang in 1520, when the expeditions of both kingdoms reached the Pacific Ocean, since there was not a set limit to the east.

- Treaty of Tordesillas : A 1494 treaty that divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa. This line of demarcation was about halfway between the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese) and the islands entered by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León).

- Christopher Columbus : An Italian explorer, navigator, and colonizer who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean under the monarchy of Spain, which led to general European awareness of the American continents.

While Portugal led European explorations of non-European territories, its neighboring fellow Iberian rival, Castile, embarked upon its own mission to create an overseas empire. It began to establish its rule over the Canary Islands, located off the West African coast, in 1402, but then became distracted by internal Iberian politics and the repelling of Islamic invasion attempts and raids through most of the 15th century. Only late in the century, following the unification of the crowns of Castile and Aragon and the completion of the reconquista , did an emerging modern Spain become fully committed to the search for new trade routes overseas. In 1492, the joint rulers conquered the Moorish kingdom of Granada, which had been providing Castile with African goods through tribute, and decided to fund Christopher Columbus’s expedition in the hope of bypassing Portugal’s monopoly on west African sea routes, to reach “the Indies” (east and south Asia) by traveling west. Twice before, in 1485 and 1488, Columbus had presented the project to king John II of Portugal, who rejected it.

Columbus’s Voyages

On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera with three ships: Santa María , Pinta ( the Painted ) and Santa Clara . Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands, where he restocked for what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean, crossing a section of the Atlantic that became known as the Sargasso Sea. Land was sighted on October 12, 1492, and Columbus called the island (now The Bahamas) San Salvador , in what he thought to be the “West Indies.” He also explored the northeast coast of Cuba and the northern coast of Hispaniola. Columbus left 39 men behind and founded the settlement of La Navidad in what is present-day Haiti.

Following the first American voyage, Columbus made three more. During the second, 1493, voyage, he enslaved 560 native Americans, in spite of the Queen’s explicit opposition to the idea. Their transfer to Spain resulted in the death and disease of hundreds of the captives. The object of the third voyage was to verify the existence of a continent that King John II of Portugal claimed was located to the southwest of the Cape Verde Islands. In 1498, Columbus left port with a fleet of six ships. He explored the Gulf of Paria, which separates Trinidad from mainland Venezuela, and then the mainland of South America. Columbus described these new lands as belonging to a previously unknown new continent, but he pictured them hanging from China. Finally, the fourth voyage, nominally in search of a westward passage to the Indian Ocean, left Spain in 1502. Columbus spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama. After his ships sustained serious damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba, Columbus and his men remained stranded on Jamaica for a year. Help finally arrived and Columbus and his men arrived in Castile in November 1504.

The Treaty of Tordesillas

Shortly after Columbus’s arrival from the “West Indies,” a division of influence became necessary to avoid conflict between the Spanish and Portuguese. An agreement was reached in 1494 with the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the world between the two powers. In the treaty, the Portuguese received everything outside Europe east of a line that ran 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (already Portuguese), and the islands reached by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Spain—Cuba, and Hispaniola). This gave them control over Africa, Asia, and eastern South America (Brazil). The Spanish (Castile) received everything west of this line, territory that was still almost completely unknown, and proved to be mostly the western part of the Americas, plus the Pacific Ocean islands.

“The First Voyage”, chromolithograph by L. Prang & Co., published by The Prang Educational Co., Boston, 1893: A scene of Christopher Columbus bidding farewell to the Queen of Spain on his departure for the New World, August 3, 1492.

Further Explorations of the Americas

After Columbus, the Spanish colonization of the Americas was led by a series of soldier-explorers, called conquistadors. The Spanish forces, in addition to significant armament and equestrian advantages, exploited the rivalries between competing indigenous peoples, tribes, and nations, some of which were willing to form alliances with the Spanish in order to defeat their more powerful enemies, such as the Aztecs or Incas—a tactic that would be extensively used by later European colonial powers. The Spanish conquest was also facilitated by the spread of diseases (e.g., smallpox), common in Europe but never present in the New World, which reduced the indigenous populations in the Americas. This caused labor shortages for plantations and public works, and so the colonists initiated the Atlantic slave trade.

One of the most accomplished conquistadors was Hernán Cortés, who led a relatively small Spanish force, but with local translators and the crucial support of thousands of native allies, achieved the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire in the campaigns of 1519-1521 (present day Mexico). Of equal importance was the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish soldiers under Francisco Pizarro, and their native allies, captured the Sapa Inca Atahualpa in the 1532 Battle of Cajamarca. It was the first step in a long campaign that took decades of fighting, but ended in Spanish victory in 1572 and colonization of the region as the Viceroyalty of Peru. The conquest of the Inca Empire led to spin-off campaigns into present-day Chile and Colombia, as well as expeditions towards the Amazon Basin.

Further Spanish settlements were progressively established in the New World: New Granada in the 1530s (later in the Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717 and present day Colombia), Lima in 1535 as the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru, Buenos Aires in 1536 (later in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in 1776), and Santiago in 1541. Florida was colonized in 1565 by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés.

The Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan died while in the Philippines commanding a Castilian expedition in 1522, which was the first to circumnavigate the globe. The Basque commander, Juan Sebastián Elcano, would lead the expedition to success. Therefore, Spain sought to enforce their rights in the Moluccan islands, which led a conflict with the Portuguese, but the issue was resolved with the Treaty of Zaragoza (1525). In 1565, the first permanent Spanish settlement in the Philippines was founded by Miguel López de Legazpi, and the service of Manila Galleons was inaugurated. The Manilla Galleons shipped goods from all over Asia across the Pacific to Acapulco on the coast of Mexico. From there, the goods were transshipped across Mexico to the Spanish treasure fleets, for shipment to Spain. The Spanish trading post of Manila was established to facilitate this trade in 1572.

England and the High Seas

Throughout the 17th century, the British established numerous successful American colonies and dominated the Atlantic slave trade, which eventually led to creating the most powerful European empire.

Explain why England was interested in establishing a maritime empire

- In 1496, King Henry VII of England, following the successes of Spain and Portugal in overseas exploration, commissioned John Cabot to lead a voyage to discover a route to Asia via the North Atlantic. Cabot sailed in 1497 and he successfully made landfall on the coast of Newfoundland but did not establish a colony.

- In 1562, the English Crown encouraged the privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa, with the aim of breaking into the Atlantic trade system. Drake carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580.

- In 1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and overseas exploration. In 1583, he claimed the harbor of Newfoundland for England, but no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who founded the colony of Roanoke, the first but failed British settlement.

- In the first decade of the 17th century, English attention shifted from preying on other nations’ colonial infrastructures to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies. The Caribbean initially provided England’s most important and lucrative colonies.

- The introduction of the 1951 Navigation Acts led to war with the Dutch Republic, which was the first war fought largely, on the English side, by purpose-built, state-owned warships. After the English monarchy was restored in 1660, Charles II re-established the Navy, but as a national institution known, since then, as “The Royal Navy.”

- Throughout the 17th century, the British established numerous successful American colonies, all based largely on slave labor. The colonization of the Americas and the participation in the Atlantic slave trade allowed the British to gradually build the most powerful European empire.

- Jamestown : The first permanent English settlement in the Americas, established by the Virginia Company of London as “James Fort” on May 4, 1607, and considered permanent after brief abandonment in 1610. It followed several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke.

- Plymouth : An English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691, first surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement served as the capital of the colony and at its height, it occupied most of the southeastern portion of the modern state of Massachusetts.

- Roanoke : Also known as the Lost Colony; a late 16th-century attempt by Queen Elizabeth I to establish a permanent English settlement in the Americas. The colony was founded by Sir Walter Raleigh. The colonists disappeared during the Anglo-Spanish War, three years after the last shipment of supplies from England.

- Navigation Acts : A series of English laws that restricted the use of foreign ships for trade between every country except England. They were first enacted in 1651, and were repealed nearly 200 years later in 1849. They reflected the policy of mercantilism, which sought to keep all the benefits of trade inside the empire, and minimize the loss of gold and silver to foreigners.

- First Anglo-Dutch War : A 1652-1654 conflict fought entirely at sea between the navies of the Commonwealth of England and the United Provinces of the Netherlands. Caused by disputes over trade, the war began with English attacks on Dutch merchant shipping, but expanded to vast fleet actions. Ultimately, it resulted in the English Navy gaining control of the seas around England, and forced the Dutch to accept an English monopoly on trade with England and her colonies.

The foundations of the British Empire were laid when England and Scotland were separate kingdoms. In 1496, King Henry VII of England, following the successes of Spain and Portugal in overseas exploration, commissioned John Cabot (Venetian born as Giovanni Caboto) to lead a voyage to discover a route to Asia via the North Atlantic. Spain put limited efforts into exploring the northern part of the Americas, as its resources were concentrated in Central and South America where more wealth had been found. Cabot sailed in 1497, five years after Europeans reached America, and although he successfully made landfall on the coast of Newfoundland (mistakenly believing, like Christopher Columbus, that he had reached Asia), there was no attempt to found a colony. Cabot led another voyage to the Americas the following year, but nothing was heard of his ships again.

The Early Empire

No further attempts to establish English colonies in the Americas were made until well into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, during the last decades of the 16th century. In the meantime, the Protestant Reformation had turned England and Catholic Spain into implacable enemies. In 1562, the English Crown encouraged the privateers John Hawkins and Francis Drake to engage in slave-raiding attacks against Spanish and Portuguese ships off the coast of West Africa, with the aim of breaking into the Atlantic trade system. Drake carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580, and was the first to complete the voyage as captain while leading the expedition throughout the entire circumnavigation. With his incursion into the Pacific, he inaugurated an era of privateering and piracy in the western coast of the Americas—an area that had previously been free of piracy.

In 1578, Elizabeth I granted a patent to Humphrey Gilbert for discovery and overseas exploration. That year, Gilbert sailed for the West Indies with the intention of engaging in piracy and establishing a colony in North America, but the expedition was aborted before it had crossed the Atlantic. In 1583, he embarked on a second attempt, on this occasion to the island of Newfoundland whose harbor he formally claimed for England, although no settlers were left behind. Gilbert did not survive the return journey to England, and was succeeded by his half-brother, Walter Raleigh, who was granted his own patent by Elizabeth in 1584. Later that year, Raleigh founded the colony of Roanoke on the coast of present-day North Carolina, but lack of supplies caused the colony to fail.

Empire in the Americas

In 1603, James VI, King of Scots, ascended (as James I) to the English throne, and in 1604 negotiated the Treaty of London, ending hostilities with Spain. Now at peace with its main rival, English attention shifted from preying on other nations’ colonial infrastructures, to the business of establishing its own overseas colonies. The Caribbean initially provided England’s most important and lucrative colonies. Colonies in Guiana, St Lucia, and Grenada failed but settlements were successfully established in St. Kitts (1624), Barbados (1627), and Nevis (1628). The colonies soon adopted the system of sugar plantations, successfully used by the Portuguese in Brazil, which depended on slave labor, and—at first—Dutch ships, to sell the slaves and buy the sugar. To ensure that the increasingly healthy profits of this trade remained in English hands, Parliament decreed in the 1651 Navigation Acts that only English ships would be able to ply their trade in English colonies. In 1655, England annexed the island of Jamaica from the Spanish, and in 1666 succeeded in colonizing the Bahamas.

African slaves working in 17th-century Virginia (tobacco cultivation), by an unknown artist, 1670

In 1672, the Royal African Company was inaugurated, receiving from King Charles a monopoly of the trade to supply slaves to the British colonies of the Caribbean. From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies and later in North America. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic.

The introduction of the Navigation Acts led to war with the Dutch Republic. In the early stages of this First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654), the superiority of the large, heavily armed English ships was offset by superior Dutch tactical organization. English tactical improvements resulted in a series of crushing victories in 1653, bringing peace on favorable terms. This was the first war fought largely, on the English side, by purpose-built, state-owned warships. After the English monarchy was restored in 1660, Charles II re-established the navy, but from this point on, it ceased to be the personal possession of the reigning monarch, and instead became a national institution, with the title of “The Royal Navy.”

England’s first permanent settlement in the Americas was founded in 1607 in Jamestown, led by Captain John Smith and managed by the Virginia Company. Bermuda was settled and claimed by England as a result of the 1609 shipwreck there of the Virginia Company’s flagship. The Virginia Company’s charter was revoked in 1624 and direct control of Virginia was assumed by the crown, thereby founding the Colony of Virginia. In 1620, Plymouth was founded as a haven for puritan religious separatists, later known as the Pilgrims. Fleeing from religious persecution would become the motive of many English would-be colonists to risk the arduous trans-Atlantic voyage; Maryland was founded as a haven for Roman Catholics (1634), Rhode Island (1636) as a colony tolerant of all religions, and Connecticut (1639) for Congregationalists. The Province of Carolina was founded in 1663. With the surrender of Fort Amsterdam in 1664, England gained control of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, renaming it New York. In 1681, the colony of Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn. The American colonies were less financially successful than those of the Caribbean, but had large areas of good agricultural land and attracted far larger numbers of English emigrants who preferred their temperate climates.

From the outset, slavery was the basis of the British Empire in the West Indies. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, Britain was responsible for the transportation of 3.5 million African slaves to the Americas, a third of all slaves transported across the Atlantic. In the British Caribbean, the percentage of the population of African descent rose from 25% in 1650 to around 80% in 1780, and in the 13 Colonies from 10% to 40% over the same period (the majority in the southern colonies). For the slave traders, the trade was extremely profitable, and became a major economic mainstay.

Map of the British colonies in North America, 1763 to 1775. First published in: Shepherd, William Robert (1911) “The British Colonies in North America, 1763–1765” in Historical Atlas, New York, United States: Henry Holt and Company, p. 194.

Although Britain was relatively late in its efforts to explore and colonize the New World, lagging behind Spain and Portugal, it eventually gained significant territories in North America and the Caribbean.

French Explorers

France established colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and India in the 17th century, and while it lost most of its American holdings to Spain and Great Britain before the end of the 18th century, it eventually expanded its Asian and African territories in the 19th century.

Describe some of the discoveries made by French explorers

- Competing with Spain, Portugal, the Dutch Republic, and later Britain, France began to establish colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and India in the 17th century. Major French exploration of North America began under the rule of Francis I of France. In 1524, he sent Italian-born Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the region between Florida and Newfoundland for a route to the Pacific Ocean.

- In 1534, Francis sent Jacques Cartier on the first of three voyages to explore the coast of Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence River. Cartier founded New France and was the first European to travel inland in North America.

- Cartier attempted to create the first permanent European settlement in North America at Cap-Rouge (Quebec City) in 1541, but the settlement was abandoned the next year. A number of other failed attempts to establish French settlements in North America followed throughout the rest of the 16th century.

- Prior to the establishment of the 1663 Sovereign Council, the territories of New France were developed as mercantile colonies. It was only after 1665 that France gave its American colonies the proper means to develop population colonies comparable to that of the British. By the first decades of the 18th century, the French created and controlled a number of settlement colonies in North America.

- As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies.

- While the French quite rapidly lost nearly all of its colonial gains in the Americas, their colonial expansion also covered territories in Africa and Asia where France grew to be a major colonial power in the 19th century.

- Sovereign Council : A governing body in New France. It acted as both Supreme Court for the colony of New France and as a policy making body, although, its policy role diminished over time. Though officially established in 1663 by King Louis XIV, it was not created whole cloth, but rather evolved from earlier governing bodies.

- mercantile colonies : Colonies that sought to derive the maximum material benefit from the colony, for the homeland, with a minimum of imperial investment in the colony itself. The mercantilist ideology at its foundations was embodied in New France through the establishment under Royal Charter of a number of corporate trading monopolies.

- New France : The area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534, and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763. At its peak in 1712, the territory extended from Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains, and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, including all the Great Lakes of North America.

- Carib Expulsion : The French-led ethnic cleansing that terminated most of the Carib population in 1660 from present-day Martinique. This followed the French invasion in 1635 and its conquest of the people on the Caribbean island, which made it part of the French colonial empire.

The French in the New World: New France

Competing with Spain, Portugal, the United Provinces (the Dutch Republic), and later Britain, France began to establish colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and India in the 17th century. The French first came to the New World as explorers, seeking a route to the Pacific Ocean and wealth. Major French exploration of North America began under the rule of Francis I of France. In 1524, Francis sent Italian-born Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the region between Florida and Newfoundland for a route to the Pacific Ocean. Verrazzano gave the names Francesca and Nova Gallia to the land between New Spain and English Newfoundland, thus promoting French interests.

In 1534, Francis sent Jacques Cartier on the first of three voyages to explore the coast of Newfoundland and the St. Lawrence River. Cartier founded New France by planting a cross on the shore of the Gaspé Peninsula. He is believed to have accompanied Verrazzano to Nova Scotia and Brazil, and was the first European to travel inland in North America, describing the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, which he named “The Country of Canadas” after Iroquois names, and claiming what is now Canada for France. He attempted to create the first permanent European settlement in North America at Cap-Rouge (Quebec City) in 1541 with 400 settlers, but the settlement was abandoned the next year. A number of other failed attempts to establish French settlement in North America followed throughout the rest of the 16th century.

Portrait of Jacques Cartier by Théophile Hamel (1844), Library and Archives Canada (there are no known paintings of Cartier that were created during his lifetime): In 1534, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in the Gaspé Peninsula and claimed the land in the name of King Francis I. It was the first province of New France. However, initial French attempts at settling the region met with failure.

Although, through alliances with various Native American tribes, the French were able to exert a loose control over much of the North American continent, areas of French settlement were generally limited to the St. Lawrence River Valley. Prior to the establishment of the 1663 Sovereign Council, the territories of New France were developed as mercantile colonies. It was only after 1665 that France gave its American colonies the proper means to develop population colonies comparable to that of the British. By the first decades of the 18th century, the French created and controlled such colonies as Quebec, La Baye des Puants (present-day Green Bay), Ville-Marie (Montreal), Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit (modern-day Detroit), or La Nouvelle Orléans (New Orleans) and Baton Rouge. However, there was relatively little interest in colonialism in France, which concentrated on dominance within Europe, and for most of its history, New France was far behind the British North American colonies in both population and economic development. Acadia itself was lost to the British in 1713.

In 1699, French territorial claims in North America expanded still further, with the foundation of Louisiana in the basin of the Mississippi River. The extensive trading network throughout the region connected to Canada through the Great Lakes, was maintained through a vast system of fortifications, many of them centered in the Illinois Country and in present-day Arkansas.

Map of North America (1750): France (blue), Britain (pink), and Spain (orange)

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534, and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763. At its peak in 1712, the territory of New France extended from Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains, and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico, including all the Great Lakes of North America.

The West Indies

As the French empire in North America grew, the French also began to build a smaller but more profitable empire in the West Indies. Settlement along the South American coast in what is today French Guiana began in 1624, and a colony was founded on Saint Kitts in 1625. Colonies in Guadeloupe and Martinique were founded in 1635 and on Saint Lucia in 1650. The food-producing plantations of these colonies were built and sustained through slavery, with the supply of slaves dependent on the African slave trade. Local resistance by the indigenous peoples resulted in the Carib Expulsion of 1660.

France’s most important Caribbean colonial possession was established in 1664, when the colony of Saint-Domingue (today’s Haiti) was founded on the western half of the Spanish island of Hispaniola. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue grew to be the richest sugar colony in the Caribbean. The eastern half of Hispaniola (today’s Dominican Republic) also came under French rule for a short period, after being given to France by Spain in 1795.

In the middle of the 18th century, a series of colonial conflicts began between France and Britain, which ultimately resulted in the destruction of most of the first French colonial empire and the near complete expulsion of France from the Americas.

Africa and Asia

French colonial expansion wasn’t limited to the New World. In Senegal in West Africa, the French began to establish trading posts along the coast in 1624. In 1664, the French East India Company was established to compete for trade in the east. With the decay of the Ottoman Empire, in 1830 the French seized Algiers, thus beginning the colonization of French North Africa. Colonies were also established in India in Chandernagore (1673) and Pondichéry in the south east (1674), and later at Yanam (1723), Mahe (1725), and Karikal (1739). Finally, colonies were founded in the Indian Ocean, on the Île de Bourbon (Réunion, 1664), Isle de France (Mauritius, 1718), and the Seychelles (1756).

While the French never rebuilt its American gains, their influence in Africa and Asia expanded significantly over the course of the 19th century.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by : Boundless.com. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Maritime Republics. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_republics . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Marco Polo. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marco_Polo . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Age of Discovery. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Pax Mongolica. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pax_Mongolica . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tabula Rogeriana. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabula_Rogeriana . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Marco Polo traveling. Provided by : Wikimedia . Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marco_Polo_traveling.JPG . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Portugese Exploration. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_discoveries . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cape of Good Hope. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cape_of_Good_Hope . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Vasco da Gama. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vasco_da_Gama . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Age of Discovery. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery#Portuguese_exploration . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ferdinand Magellan. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Magellan . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Gama Route 1. Provided by : Wikimedia . Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gama_route_1.png . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- How Portugal became the first global sea power. Located at : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcdO0QTmxIU . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Standard YouTube license

- Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_conquest_of_the_Aztec_Empire . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyages_of_Christopher_Columbus . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Christopher Columbus. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christopher_Columbus . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Treaty of Zaragoza. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Zaragoza . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Treaty of Tordesillas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Tordesillas . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reconquista. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reconquista . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spanish Empire. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_Empire . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_conquest_of_the_Inca_Empire . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Spanish colonization of the Americas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_colonization_of_the_Americas . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- First Voyage, Departure for the New World, August 3, 1492. Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_Voyage,_Departure_for_the_New_World,_August_3,_1492.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Navigation Acts. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Navigation_Acts . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Francis Drake. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Drake . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- First Anglo-Dutch War. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Anglo-Dutch_War . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Age of Discovery. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Age_of_Discovery . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Royal Navy. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Navy . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Jamestown, Virginia. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jamestown,_Virginia . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Roanoke Colony. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roanoke_Colony . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Plymouth Colony. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plymouth_Colony . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- British Empire. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tobacco_cultivation_Virginia_ca._1670.jpg. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:Tobacco_cultivation_(Virginia,_ca._1670).jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1280px-British_colonies_1763-76_shepherd1923.PNG. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:British_colonies_1763-76_shepherd1923.PNG . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Mercantilism. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercantilism . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- French colonization of the Americas. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_colonization_of_the_Americas . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- New France. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_France . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- French colonial empire. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_colonial_empire . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sovereign Council of New France. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sovereign_Council_of_New_France . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Carib Expulsion. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carib_Expulsion . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 1024px-Nouvelle-France_map-en.svg.png. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_colonization_of_the_Americas#/media/File:Nouvelle-France_map-en.svg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Cartier.png. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_colonization_of_the_Americas#/media/File:Cartier.png . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Privacy Policy

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Europe and the age of exploration.

Salvator Mundi

Albrecht Dürer

The Celestial Map- Northern Hemisphere

Astronomical table clock

Astronomicum Caesareum

Michael Ostendorfer

Mirror clock

Movement attributed to Master CR

Portable diptych sundial

Hans Tröschel the Elder

Celestial globe with clockwork

Gerhard Emmoser

The Celestial Globe-Southern Hemisphere

James Voorhies Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2002

Artistic Encounters between Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas The great period of discovery from the latter half of the fifteenth through the sixteenth century is generally referred to as the Age of Exploration. It is exemplified by the Genoese navigator, Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), who undertook a voyage to the New World under the auspices of the Spanish monarchs, Isabella I of Castile (r. 1474–1504) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (r. 1479–1516). The Museum’s jerkin ( 26.196 ) and helmet ( 32.132 ) beautifully represent the type of clothing worn by the people of Spain during this period. The age is also recognized for the first English voyage around the world by Sir Francis Drake (ca. 1540–1596), who claimed the San Francisco Bay for Queen Elizabeth ; Vasco da Gama’s (ca. 1460–1524) voyage to India , making the Portuguese the first Europeans to sail to that country and leading to the exploration of the west coast of Africa; Bartolomeu Dias’ (ca. 1450–1500) discovery of the Cape of Good Hope; and Ferdinand Magellan’s (1480–1521) determined voyage to find a route through the Americas to the east, which ultimately led to discovery of the passage known today as the Strait of Magellan.

To learn more about the impact on the arts of contact between Europeans, Africans, and Indians, see The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600 , Afro-Portuguese Ivories , African Christianity in Kongo , African Christianity in Ethiopia , The Art of the Mughals before 1600 , and the Visual Culture of the Atlantic World .

Scientific Advancements and the Arts in Europe In addition to the discovery and colonization of far off lands, these years were filled with major advances in cartography and navigational instruments, as well as in the study of anatomy and optics. The visual arts responded to scientific and technological developments with new ideas about the representation of man and his place in the world. For example, the formulation of the laws governing linear perspective by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) in the early fifteenth century, along with theories about idealized proportions of the human form, influenced artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Masters of illusionistic technique, Leonardo and Dürer created powerfully realistic images of corporeal forms by delicately rendering tendons, skin tissues, muscles, and bones, all of which demonstrate expertly refined anatomical understanding. Dürer’s unfinished Salvator Mundi ( 32.100.64 ), begun about 1505, provides a unique opportunity to see the artist’s underdrawing and, in the beautifully rendered sphere of the earth in Christ’s left hand, metaphorically suggests the connection of sacred art and the realms of science and geography.

Although the Museum does not have objects from this period specifically made for navigational purposes, its collection of superb instruments and clocks reflects the advancements in technology and interest in astronomy of the time, for instance Petrus Apianus’ Astronomicum Caesareum ( 25.17 ). This extraordinary Renaissance book contains equatoria supplied with paper volvelles, or rotating dials, that can be used for calculating positions of the planets on any given date as seen from a given terrestrial location. The celestial globe with clockwork ( 17.190.636 ) is another magnificent example of an aid for predicting astronomical events, in this case the location of stars as seen from a given place on earth at a given time and date. The globe also illustrates the sun’s apparent movement through the constellations of the zodiac.

Portable devices were also made for determining the time in a specific latitude. During the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the combination of compass and sundial became an aid for travelers. The ivory diptych sundial was a specialty of manufacturers in Nuremberg. The Museum’s example ( 03.21.38 ) features a multiplicity of functions that include giving the time in several systems of counting daylight hours, converting hours read by moonlight into sundial hours, predicting the nights that would be illuminated by the moon, and determining the dates of the movable feasts. It also has a small opening for inserting a weather vane in order to determine the direction of the wind, a feature useful for navigators. However, its primary use would have been meteorological.

Voorhies, James. “Europe and the Age of Exploration.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/expl/hd_expl.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Levenson, Jay A., ed. Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration . Exhibition catalogue. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Vezzosi, Alessandro. Leonardo da Vinci: The Mind of the Renaissance . New York: Abrams, 1997.

Additional Essays by James Voorhies

- Voorhies, James. “ Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Paul Cézanne (1839–1906) .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ School of Paris .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Art of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Naples .” (October 2003)

- Voorhies, James. “ Elizabethan England .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and His Circle .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Fontainebleau .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Post-Impressionism .” (October 2004)

- Voorhies, James. “ Domestic Art in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

- Voorhies, James. “ Surrealism .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain

- European Exploration of the Pacific, 1600–1800

- The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600

- Trade Relations among European and African Nations

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- African Christianity in Ethiopia

- African Influences in Modern Art

- Anatomy in the Renaissance

- Arts of the Mission Schools in Mexico

- Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World

- Birds of the Andes

- Dualism in Andean Art

- European Clocks in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

- Gold of the Indies

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- Islamic Art and Culture: The Venetian Perspective

- Ivory and Boxwood Carvings, 1450–1800

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

- The Manila Galleon Trade (1565–1815)

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Polychrome Sculpture in Spanish America

- The Solomon Islands

- Talavera de Puebla

- Venice and the Islamic World: Commercial Exchange, Diplomacy, and Religious Difference

- Visual Culture of the Atlantic World

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 15th Century A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- Architecture

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Cartography

- Central America

- Central Europe

- Colonial American Art

- Colonial Latin American Art

- European Decorative Arts

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Guinea Coast

- Iberian Peninsula

- Mesoamerican Art

- North America

- Printmaking

- Renaissance Art

- Scientific Instrument

- South America

- Southeast Asia

- Western Africa

- Western North Africa (The Maghrib)

Artist or Maker

- Apianus, Petrus

- Bos, Cornelis

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Emmoser, Gerhard

- Gevers, Johann Valentin

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Ostendorfer, Michael

- Troschel, Hans, the Elder

- Zündt, Matthias

Online Features

- 82nd & Fifth: “Celestial” by Clare Vincent

- MetCollects: “ Ceremonial ewer “

The Age of Discovery: A New World Dawns

- Read Later

The Age of Discovery (also known as the Age of Exploration) refers to an exciting era in European history when a number of extensive overseas voyages took place. This period lasted roughly from the beginning of the 15th century until the middle of the 17th century and is most famously associated with Portugal and Spain, though many other regions were just as curious and set out on their own journeys of discovery around the world.

The Age of Discovery is also said to have ‘spread’ to Northern Europe and Russia, since these countries conducted their own explorations as well, though they set out much later than the Spanish and Portuguese. The Age of Discovery was brought about by a combination of several factors and had an impact not only on the history of Europe, but on the whole world.

Major Factors Behind the Age of Discovery

Trade was an important factor that led to the Age of Discovery. Around the beginning of the 13th century, the Mongol Empire was established by Genghis Khan. This was the largest contiguous land empire in history and stretched from China in the east to Central Europe in the west. Thanks to the Mongol Empire, trade flowed between the East and West via the Silk Road .

- Did This Ancient Explorer Make It to The Arctic In 325 BC?

- Remorseless Chronicles of Slaughter: Fatal First Contact Between Ancient Greece and the Tribes of India